Introducing Bernard Lonergan’s Philosophical Proof for God

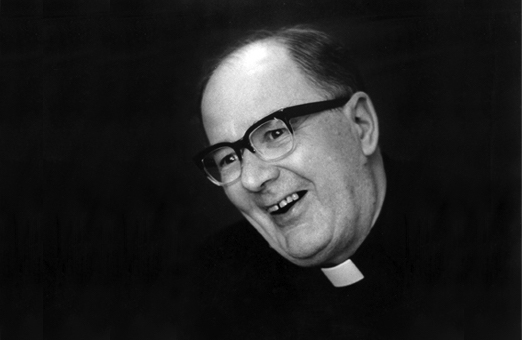

by Fr. Robert Spitzer

Filed under The Existence of God

(NOTE: This it the first of a three part series on Bernard Lonergan's philosophical proof for God. We'll share the second and third parts on Wednesday and Friday, respectively.)

Introduction

Bernard Lonergan was a Canadian Jesuit priest, philosopher, and theologian, regarded by many as one of the most important thinkers of the 20th century. He articulated a philosophical proof for God's existence which may be stated as follows:

If all reality is completely intelligible, then God exists.

But all reality is completely intelligible.

Therefore, God exists.1

We will first prove the minor premise—“all reality is completely intelligible” (Section I)—and then move to the major premise—“if all reality is completely intelligible, then God exists” (Sections II-V).

I. Proof of the Minor Premise (“All reality is completely intelligible”)

Step #1—“All Reality must have at least one uncaused reality that exists through itself.”

If there were not at least one uncaused reality in “all reality,” then “all reality” would be constituted by only caused realities – that is, realities that require a cause to exist. This means that all reality would collectively require a cause in order to exist – meaning all reality would not exist – because the cause necessary for it to exist would not be real (i.e. would not be part of “all reality”). Therefore, if there is not at least one uncaused reality that exists through itself in “all reality,” there would be absolutely nothing in existence. But this is clearly contrary to fact, and so there must exist at least one uncaused reality that exists through itself in “all reality.”

It should be noted that it does not matter if one postulates an infinite number of caused realities in “all reality.” If there is not at least one uncaused reality (existing through itself) in “all reality,” this infinite number of realities (collectively) would still not be able to exist, because the cause necessary for them to exist would still not be real – it would not be part of “all reality.”

Step #2—“An Uncaused Reality Must Be a Final and Sufficient Correct Answer to All Coherent Questions”—Making ‘All Reality’ Completely Intelligible.

There is another consequence of the existence of at least one uncaused reality. An uncaused reality not only enables “all reality” to exist, but also enables “all reality” to be completely intelligible. This can be proven in three steps:

Step #2.A

Using the above logic, we can also deduce that every real cause-effect series must also have an uncaused reality. If the series did not have an uncaused reality, it would not exist, because it would be constituted only by realities that must be caused in order to exist, and as we saw above, this means that the entire series (even an infinite series) would collectively need a cause to exist. But if an uncaused cause is not in the collective causes and effects in the series, then the collective cause-effect series would be nonexistent—merely hypothetical. Furthermore, this uncaused reality must ultimately terminate every real cause-effect series, because when the cause-effect series reaches a reality that does not need a cause to exist (because it exists through itself), there is by definition no cause prior to it.2 Therefore, an uncaused reality must terminate every real cause-effect series, and as such, no real cause-effect series continues infinitely. Thus, all real cause-effect series are finite insofar as they are terminated by an uncaused reality.

Step #2.B

At this point, Lonergan recognizes something special about a terminating uncaused reality. It is not only an ultimate cause and terminus a quo (the terminus from which any cause-effect series begins), it is also the ultimate answer to all questions of causal explanation – “Why is it so?” What Lonergan sees clearly is that intelligibility follows ontology. By “intelligibility” Lonergan means what makes something capable of being understood – that is what makes something “questionable” and “answerable.” If any intelligent inquirer can ask a coherent question about something, and that question has a correct answer that comes from “that something,” then “that something” is intelligible – it is capable of providing a correct answer to coherent questions asked about it.

What Lonergan sees in Chapter 19 of Insight3 is that the terminus a quo (beginning) of any cause-effect series must also be the final and sufficient answer to the question for causal explanation – “Why is it so?” So why is an uncaused reality a final and sufficient answer to this question? Inasmuch as an uncaused reality terminates any cause-effect series, it also terminates the possible answers to the question “Why is it so?” asked about that series; and since an uncaused reality exists through itself, it must also explain itself through itself. It is its own answer to the question of its existence. Thus, the terminating answer to the question “Why is it so?” about any cause-effect series is also a completely self-explanatory answer. In this sense, it is both the terminating and sufficient answer to the question, “Why is it so?” for any cause-effect series.

Thus, we will always reach a sufficient end to our questioning for causal explanation (“Why is it so?”), because we will ultimately arrive at an uncaused reality existing through itself – without which all reality would be nothing. Therefore, an uncaused reality must be the final and sufficient answer to every question of causation (“Why is it so?”).

This has a further consequence for Lonergan, because the final answer to the question “Why is it so?” must also be the final answer to all other questions – as we shall see in Step 2.C.

Step #2.C

If there must be a final and sufficient answer to the question “Why is it so?”, there must also be a final and sufficient answer to every other question (e.g. “What?”, “Where?”, “When?”, “How does it operate?” etc.), because the latter is grounded in (dependent on) the former. Without an ultimate cause of existence, there would be literally nothing to be intelligible. There cannot be questions for intelligibility (e.g. “What is it?”) that go beyond the final (ultimate) cause of existence. If there were such questions, their answers would have to be “nothing.” Therefore, a final (ultimate) answer to the question “Why is it so?” must ground the final (ultimate) answer to every other question. The answers to all possible questions must terminate in the final answer to the question “Why is it so?” Since there must exist a final and sufficient answer to the question “Why is it so?” (an uncaused reality existing through itself), there must also be a final and sufficient answer to every other question about reality. The complete set of correct answers to the complete set of questions really must exist – and reality, as Lonergan asserts, must therefore be completely intelligible.4

II. Proof of the Major Premise (“If all reality is completely intelligible, God exists”)5

Why does Lonergan believe that if all reality is completely intelligible, then God (i.e. a unique unrestricted reality which is an unrestricted act of thinking) exists? As we saw in the proof of the Minor Premise, all reality must include an “uncaused reality that exists through itself.” Without at least one uncaused reality, there would be nothing in all reality. This uncaused reality brings finality to the answers to every question that can be asked about all reality – and so makes all reality completely intelligible. Lonergan recognizes that such an uncaused reality must also be unrestricted in its intelligibility, and this requires that it be unique (one and only one) as well as an unrestricted act of thinking, and the Creator of the rest of reality. The proof of these contentions is summarized below in this section and in Sections III, IV, and V.

We now turn to the proof of the first of these contentions – namely, that an “uncaused reality existing through itself” must be unrestricted in its intelligibility. This may be shown in two steps:

Step #1

An uncaused reality must be unrestricted in its explicability (its capacity to explain itself from within itself). If it were restricted in its capacity to explain itself, then its existence would be at least partially unexplained, which contradicts the nature of a reality that exists through itself (an uncaused reality). Put the other way around, a reality that exists through itself (an uncaused reality) cannot be restricted in its capacity to explain its existence (because that would be a contradiction); therefore, it must be unrestricted in its capacity to explain its existence and so also unrestricted in its explicability.

Step #2

If a reality is unrestricted in its explicability, it must also be unrestricted in its intelligibility. We were given a hint about the proof of this contention in the Minor Premise when it was shown that the final answer to the question “Why is it so?” must also be the final answer to all other questions – that is, that the answers to all questions must terminate in an uncaused reality existing through itself. Lonergan realizes that not only the finality of intelligibility follows from the finality of explicability (existence), but also that the unrestrictedness of intelligibility follows from the unrestrictedness of explicability (existence).6

Let’s begin with a logical examination of this contention – “If an uncaused reality is unrestricted in its explicability, then it will be unrestricted in its intelligibility.” This can be analyzed by looking at the necessary logical implication of this proposition – namely, that if an uncaused reality is not unrestricted (i.e. is restricted) in its intelligibility, then it cannot be unrestricted (i.e. it must be restricted) in its explicability (modus tollens). In brief, if a reality is restricted in its intelligibility, then it will also be restricted in its explicability. As we saw in Step #1 above, an uncaused reality must be unrestricted in its explicability, otherwise it would be a contradictory state of affairs – “A reality existing through itself that cannot fully explain its existence.” It now remains to show why a restriction in intelligibility implies a restriction of explicability.

What does it mean for a reality to be restricted in intelligibility? In Lonerganian terms, it means that more questions can be asked about a reality than can be answered by the information within it. This means that the answer to some questions about what a thing is, or how it operates, where it occurs, or when it occurs, etc., are explained by realities beyond the reality in question. For example, I cannot completely answer what an electron is without reference to the electromagnetic field through which it operates (which is beyond any given electron). Similarly, I cannot answer questions about where and when an electron will occur without making reference to the space-time field, the specific electromagnetic field, and other electromagnetic constituents in the region (which are all beyond a particular electron). I cannot even understand how an electron operates without making reference to electromagnetic fields and other electromagnetic constituents (which are beyond a particular electron).

It may be asked whether every reality that is restricted in intelligibility must depend on something beyond itself for its intelligibility. If it did not depend on something beyond itself for its intelligibility, and its intelligibility is not ultimately grounded in itself, then its intelligibility would have to be grounded in nothing. But this is incoherent – because it means that the intelligibility of a reality is grounded in the unreal – which is tantamount to saying that a reality has the intelligibility of nothing.

In Lonerganian terms, if a reality is restricted in its intelligibility, then there is insufficient information in it to answer all coherent questions that can be asked about it – it poses more coherent questions than it can answer by itself. In the example of the electron, we saw that the answer to the questions “What is it?” “How does it operate?” “Where is it?” and “When is it?” etc., depend on the intelligibility of the realities beyond the electron. Does every restrictedly intelligible reality function this way? Do the answers to the coherent questions -- which are not answered by a restrictedly intelligible reality – have to be grounded in realities beyond it – like the electron? They would have to be if we are to avoid the paradox of the intelligibility of a reality being grounded in the unreal. As we saw above, this is tantamount to saying that a reality has the intelligibility of nothing – a contradiction. This means that the unanswered questions about a restrictedly intelligible reality will have to have their answers in realities beyond it – like the electron.

Therefore, if a reality is restricted in its intelligibility, it does not explain some aspect of itself, which implies that its explanation lies in something beyond itself. In short, if a reality is restricted in its intelligibility, it is also restricted in its explicability.

As noted in Step #1, an uncaused reality cannot be restricted in its explicability, because it is not dependent on anything beyond itself for its explanation – it exists through itself. To suggest otherwise is to argue a contradiction – “that a reality existing through itself cannot fully explain its existence.” Now, if a restriction of intelligibility implies that a reality is dependent on realities beyond itself for its explanation, and an uncaused reality by definition is not dependent on any reality beyond itself for its explanation, then an uncaused reality cannot be restricted in its intelligibility. It must therefore be unrestricted in its intelligibility.7

Related Posts

Notes:

- See Bernard Lonergan 1992, Insight: A Study of Human Understanding in Collected Works of Bernard Lonergan 3, ed. by Frederick E. Crowe and Robert M. Doran (Toronto: University of Toronto Press) p. 695. ↩

- This pertains to both ontological and temporal priority. Thus, there is no ontologically prior or temporally prior cause to an uncaused reality – by definition. ↩

- See Lonergan 1992 pp 674-680. ↩

- See the extended treatment in Lonergan 1992, pp. 674-680. ↩

- This proof may be found in Lonergan 1992, pp. 692-698. ↩

- See Lonergan 1992, pp. 674-679. ↩

- Another way of explaining why unrestricted explicability implies unrestricted intelligibility is as follow. A reality that is unrestricted in its explicability will have no other logically possible alternatives to itself. It exhausts all possibilities for reality in itself. Thus, the answer to the question “Why is this reality so?” is “There is no other possibility than this reality because it exhausts all possibilities for reality within itself – and hence it also exhausts all possibilities for intelligibility within itself.” ↩

Note: Our goal is to cultivate serious and respectful dialogue. While it's OK to disagree—even encouraged!—any snarky, offensive, or off-topic comments will be deleted. Before commenting please read the Commenting Rules and Tips. If you're having trouble commenting, read the Commenting Instructions.