I’m Not a Christian, But I’m Fascinated by the Incarnation

by Tamer Nashef

Filed under Jesus

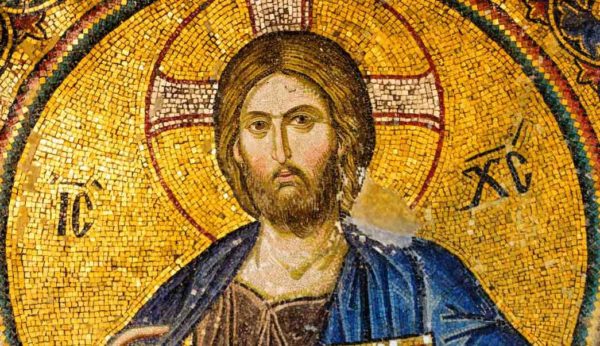

As a secular Muslim, I see the Incarnation (the embodiment of God the Son in human flesh) as one of Christianity’s most philosophically rich doctrines that has likely had a substantial impact on the evolution of the European mind. As I understand this doctrine, by inhabiting a human body and being present on earth, Christ as the Son of God not only sanctified the body and material world, but he also conferred some form of divinity upon man1 and in a sense humanized God,2 thereby bridging the hitherto yawning gulf between Creator and man.

My argument is that this key Christian doctrine gave rise in the history of European thought to favorable views of matter and of human nature and predisposed European artists, especially in the Renaissance, to celebrate the human body and to produce awe-inspiring artistic representations of not only Christ, the apostles, and the saints, but also of God the Father. Such representations would have been considered abhorrent or blasphemous in other non-Christian cultures.

True enough, despite the doctrine of the Incarnation, there was always a stream within Christianity that sought to detach itself from the world of matter, that expressed aversion to the body, and that viewed human beings as incorrigibly sinful. In his Book of Rules, St Benedict of Nursia (c. 480-c. 543), the father of Western monasticism, advised monks to “chasten the body” and to “make [themselves strangers] to the affairs of the world.”3 Italian friar and preacher St Francis of Assisi (died 1226) taught: "We should feel hatred towards our body for its vices and sinning!"4

In the 16th century, John Calvin drew a grim picture of human nature as being “blind, darkened in understanding, and full of corruption and perversity of heart.” Due to such views, especially if those of St Benedict and St Francis are taken at face value or out of context, Christianity is often unfairly characterized as a primarily otherworldly, life-negating, body-hating religion.

The doctrine of the Incarnation likely played a central role in shifting the Christian worldview away from a gloomy vision of human nature, contempt for matter/body, and absolute focus on the afterlife toward optimistic belief in human potential, appreciation of temporal existence, and concern with the here and now. Bishop Irenaeus of Lyons (130-202) criticized the Gnostic5 rejection of material reality, affirming that the body and matter were as holy as the spirit. In his refutation of iconoclasm6, Byzantine scholar John of Damascus (died 749) explained that God’s sojourn on earth as a human being for the sake of mankind’s salvation obligated him to respect matter:

“I venerate the fashioner of matter [God], who became matter [the Incarnation] for my sake and accepted to dwell in matter and through matter worked my salvation, and I will not cease from reverencing matter, through which my salvation was worked...Therefore I reverence the rest of matter and hold in respect that through which my salvation came, because it is filled with divine energy and grace.”

The Incarnation, along with the theomorphic conception of man7, probably inspired others to write in glowing terms of man’s innate worth and dignity despite the belief in man’s fallen nature. Theologian and philosopher Clement of Alexandria (died 211) is a case in point. Clement underscored the uniqueness and sacredness of man: ”For think not that stones, and stocks, and birds, and serpents are sacred things, and men are not; but, on the contrary, regard men as truly sacred, and take beasts and stones for what they are.” A century later, Bishop Gregory of Nyssa (335 – c. 395) conceived of God as “the best artist” who “forges our nature so as to make it suitable for the exercise of royalty,” adding: “Through the superiority given by the soul and through the very makeup of the body, he arranges things in such a way that man is truly fit for regal power.” Even St Augustine (died 430), who believed man was mired in sin, pointed out the aesthetic aspects of the human body, emphasizing its “beauty” and “concord,” especially the “nimbleness” of the tongue and the hands. He observed that “no part of the body has been created for the sake of utility that does not also contribute to its beauty.” He also waxed lyrical in his description of the world of matter/nature:

“Shall I speak of the manifold and various loveliness of sky, and earth, and sea; of the plentiful supply of and wonderful qualities of light; of sun, moon, and stars; of the shade of trees; of the colors and perfumes of flowers, of the multitude of birds...?”

Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274) maintained that “rational” human beings were the “most perfect to be found in all nature,” adding: "To take something away from the perfection of the creature is to abstract from the perfection of the creative power itself [i.e. God].” Indeed, though Aquinas, like Augustine before him, regarded human beings as sinful, he believed they were capable of good.

The best was yet to come in the Italian Renaissance. In Oration on the Dignity of Man (1486), one of the masterpieces of the era, Pico della Mirandola (1463-1494) describes man as “the most fortunate living thing worthy of all admiration,” “a great miracle,” and “a truly remarkable being” whose “rank” is “to be envied not only by the brutes but even by the stars and by minds beyond this world.” Catholic priest and scholar Marsilio Ficino (1433-1499) went further, arguing that “man possesses as it were almost the same genius as the Author of the heavens.” He voiced boundless optimism about human potential: “And who could deny that man could somehow also make the heavens, could he obtain the instruments and the heavenly material...?” Both the bronze sculpture David by Donatello (1386-1466), the first nude sculpture since antiquity, and the fresco painting Creation of Adam on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel by Michelangelo (1475-1564), celebrate the human body, investing it with value and dignity. The Proportions of Man8, a drawing by Italian polymath and genius Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519), reflects the artist’s fascination with the human body.

It is worth remembering that though Renaissance scholars often treated moral problems in a largely secular manner and scorned their Scholastic predecessors, they were devout Christians who studied the Bible and the writings of Church Fathers and never questioned the validity of Scripture. As is well known, religious themes9 figure prominently in Renaissance art as evident in the works of not only Michelangelo but also Masaccio (1401-1428)10, Leonardo da Vinci11, Raphael (1483-1520)12, and Pietro Perugino (1446-1523)13.

In addition, the Incarnation possibly prompted Christian theologians to develop a universalistic conception of humanity. Since Christ assumed human form, all human beings were fundamentally equal and endowed with dignity and worth that could not be taken away.14 Archbishop of Constantinople Gregory of Nazianzus (c. 329–390) advised his congregation to see prelapsarian15 equality, unity, and liberty as their model:

“I would have you look back to our primary equality of rights, not the later diversity...As far as you can, support nature, honor primeval liberty, show reverence for yourself and cover the shame of your race, help to resist sickness, offer relief to human need.”

Christian philosopher Yahya ibn ‘Adi (893-974) emphasized the unity of mankind:

“...men are one tribe...joined together by humanity. And the adornment of the divine power is in all and in each...of them, it being a rational soul...All men are really a single entity in many individuals.”

Father Domingo de Soto (died in 1560), Dominican priest and Scholastic theologian, wrote of the equality between Christians and non-Christians in terms of natural rights: “Those who are in the grace of God are not a whit better off than the sinner or the pagan in what concerns natural rights.”

Interestingly, all these lofty conceptions of human nature, a plausible product of the Incarnation and of an intellectual milieu suffused with Christian values, contrast with the views of Enlightenment philosopher and surgeon Julien Offray de La Mettrie (1709-1751).As a materialist thinker, La Mettrie downgraded the worth of human beings and knocked them off their pedestal as the pinnacle of creation. He judged that humans, whose bodies were no more than machines, were not qualitatively different to other creatures: “Man is not molded from a costlier clay; nature has used but one dough and has merely varied the leaven.” Certainly, the likes of Aquinas, Mirandola, Ficino, and Michelangelo would have begged to differ.

Related Posts

Notes:

- Athanasius of Alexandria (c. 296–298–373) argued that Christ as the Son of God “has made us sons of the Father, and deified men by becoming himself man.”

- What I mean by this is that God in Christianity is not so transcendent and sovereign as to be completely mysterious or incomprehensible to the human mind. God's handiwork, the universe, is open to rational inquiry, observation, and quantification and its laws capable of being spelled out in human language. Johannes Kepler (died 1630) compared God to an aesthetician and a geometer while Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (died 1716) and Isaac Newton (died 1727) viewed God as an “architect” and a “mechanic,” respectively. Galileo Galilei (died 1642) saw the universe as a “grand book...written in the language of mathematics, and its characters are triangles, circles, and other geometric figures without which it is humanely impossible to understand a single word of it.” The Christian God is also a rational creator who is expected to abide by objective moral categories and standards deducible by reason. That God took on bodily form probably inspired European art, especially in the Renaissance, to create human renderings of God.

- St Benedict, however, did not urge monks to fully devote their lives to contemplation or purely spiritual activities. He denounced idleness as “the enemy of the soul” and highlighted the importance of manual labor, calling on monks “to live by the labor of their hands, as our fathers and the apostles did.”

- I would hate to give the impression that the quote above encapsulates the thought of St Francis whom I personally respect for many reasons. First, he saw conscience as a key element in monastic life: “If any one of the ministers gives to his brothers an order contrary to our rule or to conscience, the brothers are not bound to obey him, for obedience cannot command sin.” Second, Francis was critical of the Crusades. In fact, he tried, albeit unsuccessfully, to convince Cardinal Pelagio Galvani, who was in charge of the 5th crusade, to make peace with the Egyptian Sultan Al-Malik al-Kamil. Francis, who travelled to Egypt to meet the sultan in person, was impressed by Muslims’ religious devotion, especially by the five daily calls to prayer. Third, Francis wrote great hymns and prayers, one of which reads:

“Lord, make me an instrument of your peace;Where there is hatred, let me sow love,Where there is injury, pardon,

Where there is doubt, faith.

Where there is despair, hope,

Where there is darkness, light,

Where there is sadness, joy.

O Divine Master, Grant that I may not so much seek

To be consoled, as to console,

To be understood, as to understand,

To be loved, as to love;

For it is in giving that we receive;

It is in pardoning that we are pardoned;

- Gnosticism refers to the beliefs and practices of a dualistic religious movement denounced as heretical by the Church. It taught that matter and corporeal reality were evil. Prominent Gnostic leaders include Valentinus and Basilides.

- Iconoclasm originated in the Byzantine Empire in the 8th and 9th centuries. It rejected the veneration of icons and the artistic depiction of Christ and the saints. The Third Council of Nicaea condemned it in 787.

- The biblical idea that man is created in the image of God.

- Also known as Vitruvian Man, reference to Roman architect Vitruvius (died 15 BC). Here it is worth noting that ancient Greco-Roman art was another source of the Renaissance celebration of the body. The medieval West’s rediscovery of a large portion of the pagan tradition of ancient Greece and Rome was a major inspiration for Renaissance artists, including the technique of perspective (representing three-dimensional objects on a two-dimensional surface). Eminent Greek artists included Euphronios, Euthymides, Myron, Phidias, Polyclitus, Praxitiles, Lysippos, and many others. The Romans borrowed art from other peoples, especially the Greeks, but they did so creatively, especially in architecture.

- Renaissance art also includes self-portraits and landscape scenes and deals with subjects from Greek and Roman mythology.

- Such as the Holy Trinity fresco.

- The last Supper.

- The Sistine Madonna.

- Delivery of the Keys, a fresco in the Sistine Chapel.

- Of course, the influence of Stoicism on Christianity in this regard (humanity as a single community and the brotherhood of all human beings) cannot be denied. Christianity’s ability to assimilate Stoic ideals (and other pagan values) was key in the development of Western civilization.

- Before the fall of man.

Note: Our goal is to cultivate serious and respectful dialogue. While it's OK to disagree—even encouraged!—any snarky, offensive, or off-topic comments will be deleted. Before commenting please read the Commenting Rules and Tips. If you're having trouble commenting, read the Commenting Instructions.