Atheism, Philosophy, and Science: An Interview with Dr. Michael Ruse

by Brandon Vogt

Filed under Atheism, Christianity and Science, Interviews

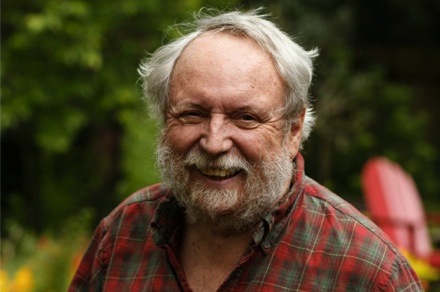

As a young undergraduate at Florida State University, studying mathematics and engineering, I had no idea that one of the world's leading philosophers of science worked just a couple buildings away. Had I known about Dr. Michael Ruse then, I would have jumped at the chance to meet him. He's since become one of my favorite atheist writers, displaying a sharp mind and a good will, free of needless polemics. (He's also not afraid to tattoo extinct marine arthropods on his arm if dared.)

This past December we finally had the chance to meet. The occasion was a special colloquium on contemporary atheism, hosted by Dr. Ruse in Tallahassee. I joined fellow Strange Notions contributor Dr. Stephen Bullivant and several other philosophers and theologians to discuss current research on unbelief. The event also featured the launch of The Oxford Handbook of Atheism, the definitive tome co-edited by Stephen and Dr. Ruse.

As a philosopher, Dr. Ruse specializes in the philosophy of biology and is well known for his work on the relationship between science and religion, the creation-evolution controversy, and the demarcation problem in science. He was born in England, studied at the University of Bristol (1962), attained his master's degree at McMaster University (1964), and then returned to the University of Bristol for his Ph.D. (1970).

Dr. Ruse graciously agreed to answer a few questions about his experiences with faith, the debate between evolution and religion, and his favorite theologians.

Q: You once testified in court, under oath, that "I am not an expert on my own religious opinions." What did you mean by that?

Dr. Ruse: Basically, what I meant was that I would be very uncomfortable being pinned down to one clear statement about my own religious beliefs. It is certainly true that I do not accept Jesus as the son of God, and that, indeed, I have great deal of trouble with the whole notion of the Christian God. I think the Christian God is an uncomfortable amalgam of Jewish and Greek thought and does not withstand careful scrutiny. It does not stand up too well. I find the notion of necessary existence, which is an essential part of the Christian God, to be incoherent. I’m also very troubled by the problem of evil.

However, whether this means that I don’t believe in anything at all is something that puzzled me when I was in court and still puzzles me some 30 years later. I am inclined therefore say that existence, including humans and their consciousness, is something of a mystery. I don’t think this necessarily means that I’m going to enjoy eternal bliss. In fact, I don’t know what any of it means.

So in that sense, I’m not an expert on my own opinion. I suppose you could call me an agnostic or skeptic, who is atheistic about traditional religions. But I would not want to go much further than that.

Q: You were raised a Quaker, and often speak fondly of how that tradition influenced you. Some high-profile atheists today suggest that any religious upbringing is a form of child abuse. How does that jive with your experience?

Dr. Ruse: As I explained recently in a piece I wrote for the online journal Aeon, I feel very strongly that my Quaker background was incredibly important in forming my personality. I was shown love and attention by my parents and their coreligionists that has lasted me all of my life. In particular, I have been taught never to accept anything just because somebody told me. I must always try to puzzle things out for myself.

At the same time I take very seriously the Quaker belief that God is in every person, interpreting this of course in a secular fashion. It has guided me through my life as a teacher, making me realize that even when I have not been particularly drawn towards certain students, nevertheless it is my obligation to treat them as being worthy of attention, no less than anyone else.

So clearly I don’t think all religious upbringing is a form of child abuse. At the same time I think sometimes it can be this. To use an analogy, children who were brought up during the Nazi era were filled with views on Jews that I think makes this training akin to child abuse, just as much as if they had been beaten. Analogously, I am inclined to think some views that children are taught in the name of religion are quite morally troublesome. I would include, for instance, views that homosexuality is in some sense evil, or if not evil in itself that the acts of homosexuals are evil. It seems to me that teaching this to a child is getting close to abuse. So yes I can think of some forms of religious training or indoctrination as forms of child abuse.

Q: One of your best known books is titled Can a Darwinian be a Christian? For those who haven't read it, what's your short answer to that question?

Dr. Ruse: As I say in my book, I think the Darwinian can be a Christian, but that it’s not easy. However, I also say that the more important things in life are never easy! I think one can find ways to reconcile Darwinism with Christian claims about Original Sin, the problem of evil, free will, and similar issues.

I think one of the biggest problems is the appearance of humans here on the Earth. I’m not sure that I solved the problem in my book. It seems to me that Christians have to accept that the appearance of humans was not pure chance, but that this was intended by God. However I see a radical indeterminacy in evolutionary thinking and I am not sure that we can guarantee the appearance of any organism, including humans. I think now I would want to try to solve the problem by invoking the notion of a multiverse. Humans would eventually have evolved, if not in our universe then in some other. Remember, God is outside space and time. So it is not as if he is waiting for any of this to happen. Obviously this is all very speculative. As I said, I don’t think it is easy to reconcile Darwinism and Christianity.

I don’t think however that the only arguments pertinent to the truth of the Christian faith are those based on science. I think philosophy and theology also have a role. I argue that when these are applied to Christianity, it can be seen that the overall position is not tenable.

An example of where I would see philosophy criticizing Christianity would be over the already-mentioned issue of necessary existence. I don’t think the idea of necessary existence makes sense. Hence, since it is so important for Christianity, I think Christianity has to be false. Notice, however, that an argument against the notion of necessary existence is not a scientific argument, but a philosophical argument. That is why I say that even if Christianity can be reconciled with science, it does not follow that Christianity is true.

Q: Many Christian theologians claim you as their favorite atheist philosopher. Who is your favorite Christian theologian?

Dr. Ruse: Well that’s a very big question. I think that if you are going to dig back in history, I’d probably want to put St. Augustine up top as my favorite theologian. I do have, however, a great respect for St Anselm. I only exclude St. Thomas Aquinas from this list because, to be honest, I don’t know enough about his writings to make a full judgment. Notice that I’m a philosopher and not a theologian so I’m not really at fault here.

If we take Christian theology closer to the present than I would certainly say I have great admiration for the English theologian of the 19th century, John Henry Newman. I think his ideas about the gradual revealing of Christianity is a most valuable tool of understanding. If you were to ask me about contemporary theologians, I was personally fond of Langdon Gilkey and much in sympathy with the kind of science-and-religion-separate view that he endorsed, often known as neo-orthodoxy.

Amongst living theologians, I am proud to call John Haught (the Catholic theologian, recently retired from Georgetown University) a good friend. I don’t think I endorse his evolutionary view of theology, influenced as he has been by Teilhard de Chardin and perhaps earlier by Alfred North Whitehead. But as an individual I like John a great deal and I find altogether admirable his determined effort to integrate evolutionary thinking into Christian theology.

Another theologian of today, of whom I am personally fond and for whom I have great admiration, is John Schneider, who used to teach at Calvin College. He lost his job for suggesting that Adam and Eve are not true and that therefore we need to reinterpret or rethink the Augustinian position on Original Sin. I think John is right about the nonexistence of Adam and Eve and I greatly admire his moral courage in asserting this, even to the point where he was dismissed from Calvin College.

Q: Let's talk about The Oxford Handbook of Atheism, which you co-edited with Strange Notions contributor Dr. Stephen Bullivant. The book is a 46-chapter, 750+ page compendium of contemporary scholarship on all kinds of topics relating to unbelief. How did the book come about?

Dr. Ruse: The Oxford Handbook of Atheism is easy to explain. I was approached by Stephen Bullivant, who was looking for a co-editor, perhaps one who was rather more established than he and who did not share his deep Christian faith. I don’t know how Stephen feels about me, but I can say that, from my perspective, it was a truly wonderful experience working with him. Stephen was an ideal editor, he knew far more about the topic than I, and we always worked harmoniously together. He did the bulk of the work, but I hope Stephen would agree that I did my share as and when required. I simply could not have done this book on my own, and I feel very privileged to have been allowed to work alongside Stephen on this project.

Q: You're very well-informed about the history and philosophy of atheism, but what new insights did you learn while compiling the Handbook?

Dr. Ruse: I’m not sure whether the real insights came from compiling the Handbook alone or more from a subsequent project that I have just completed, namely writing a single-author work for Oxford University Press entitled Atheism: What Everyone Needs to Know. (This is part of a general series “what everyone needs to know.”)

The thing which came through to me most strongly was that the atheism debate is not just a matter of epistemology, that is to say of factually right and wrong. It is and always has been an intensely moral issue. People who argue for or against atheism are deeply committed to the moral worth of what they claim. Obviously this comes through with religious believers defending their faith against atheism. But it’s equally true of atheists. One sees this most clearly in the writings of the New Atheists. A work like The God Delusion by Richard Dawkins as much a moral sermon as anything one might get from Jonathan Edwards. After all, anyone who says Christian education is child abuse is hardly stating brute empirical facts.

So I would say, as I bring this interview to an end, it is the moral dimension to the debate about atheism which strikes me most forcibly. I can also say, quite honestly, that before I started in on the Oxford Handbook and on the book I have subsequently written, I had no idea any of this would be so. I always say that the first person for whom I write is myself and never has this been truer than in the case of my writings and editing on and around the topic of atheism.

Related Posts

Note: Our goal is to cultivate serious and respectful dialogue. While it's OK to disagree—even encouraged!—any snarky, offensive, or off-topic comments will be deleted. Before commenting please read the Commenting Rules and Tips. If you're having trouble commenting, read the Commenting Instructions.