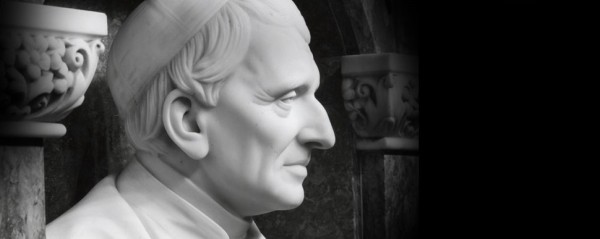

John Henry Newman: Real, Rational, Religion

by Daniel McGiffin

Filed under Belief

In the late nineteenth century, Catholic-convert Blessed John Henry Cardinal Newman published one of the all-time greatest works on the epistemology of faith. Essay in Aid of the Grammar of Assent was written in response to trends in thought widespread in 19th c. Oxford. Since the Enlightenment (and before) the Catholic Church has been criticized for the dogmatic structure of its faith and morals. People like Immanuel Kant and David Hume have spoken of dogma as if it were a leash or blinders, as if the Church believed that without its dogmas the faithful would simply run amok—or worse!—leave.

This idea about dogma is inherent in what Newman called liberalism, and it is still alive and well to this day. When I say liberalism, I am not speaking politically. Newman uses the term liberalism throughout his work, and I want to stress that I am not, and nor was he, talking about political liberalism.This “philosophical liberalism” is found on both sides of the aisle, as it were. I’d find a substitute word if I could, but the only one that comes to mind is “adogmatism,” which I think we can all agree is an ugly and stupid word.

Not sure if you’re this kind of liberal? Here’s a brief questionnaire for you:

- Do you think that reason can trump doctrine?

- Do you think no one can believe in something that he or she can’t understand?

- Do you think theological doctrine is nothing more than an opinion held by a vocal group of people?

- Do you think it’s dishonest to believe in something that hasn’t been proven?

If you answered yes to any of these, then Newman was talking about you!

Liberalism Defined

For Newman, liberalism is the belief that nothing outside of science has a certain answer, which in essence puts all religions in the “made-up stuff” bin. This is not just the claim of atheists and agnostics; it’s also common to many Protestant denominations (universalists, as opposed to exclusivists).

Newman found certain principles that he saw as fundamental to liberalism. In the appendix to his auto-biographical work, the Apologia Pro Vita Sua, Newman lists just shy of two dozen tenets of liberalism. The first four form the basis of the rest:

1. No religious tenet is important, unless reason shows it to be so.

2. No one can believe what he cannot understand.

3. No theological doctrine is anything more than an opinion which happens to be held by bodies of men.

4. It is dishonest in a man to make an act of faith in what he has not had brought home to him by actual proof.1

We all know (or are) people who hold these tenets either explicitly or implicitly. To demonstrate the rationality behind dogmatic religion, Newman reaches deep into the way we know, and lays out a comprehensive epistemological system that seeks to disprove the assertions of liberalism.

The Different Kinds of Propositions

Newman points out that there are three kinds of propositions that can be made by a person: Interrogative (a question is asked), Conditional (a conclusion is drawn) and Categorical (the proposition is asserted in itself). There are also three internal acts associated with these propositions. The internal act made with an Interrogative is doubt, a Conditional is accompanied by inference, and a Categorical statement comes with assent (assent for Newman means simply belief/acceptance). The three types of propositions, and their accompanying internal acts, are each distinct from the other.2 These form the epistemological foundation that Newman uses throughout his work, and if you don’t remember these terms as you read this, you won’t get it. I’m relying on his terms for precision of communication. This is not a proof for God’s existence, it is an explanation of the rational process of faith.

Apprehension: How to Believe in What is Not Understood

The first part of Grammar of Assent, Assent and Apprehension, addresses skeptical epistemologies with the goal of demonstrating that belief in what is not understood is not only permissible, but necessary. In Newman’s view, what is necessary for assent is not understanding the proposition, but apprehending it (The reason for this distinction is that the term understanding is “of uncertain meaning, standing sometimes for the faculty or act of conceiving a proposition, sometimes for that of comprehending it, neither of which come into the sense of apprehension.” 3 Apprehension “is simply an intelligent acceptance of the idea, or of the fact which a proposition enunciates”,4 and it allows us to internally assent to what has been externally asserted.

Newman classifies apprehension into two kinds, notional and real, corresponding to abstract concepts and concrete experience, respectively. We can notionally apprehend a proposition such as “London is a beautiful city” without having been to London, since we have in our mind the concept of “beauty” and the concept of “city”, but real apprehension would require us to have been to London, and to recollect our mental image of London as beautiful. After several related experiences, we begin to form general rules about individual propositions, abstracting broader and more general propositions from our individual experiences, and these are what we notionally apprehend.

Newman classifies apprehension into two kinds, notional and real, corresponding to abstract concepts and concrete experience, respectively. We can notionally apprehend a proposition such as “London is a beautiful city” without having been to London, since we have in our mind the concept of “beauty” and the concept of “city”, but real apprehension would require us to have been to London, and to recollect our mental image of London as beautiful. After several related experiences, we begin to form general rules about individual propositions, abstracting broader and more general propositions from our individual experiences, and these are what we notionally apprehend.

Here of course it is easy to see how Newman has structured his argument along similar lines as Hume. For both, experience is the starting point of our knowledge, and our apprehension (though Hume doesn’t use that term) is surer of the former than the latter. Newman comes to the opposite conclusion of Hume though, and the lack of clarity surrounding the term “understanding”, is crucial as to why.

According to Newman, assent to the dogmata of the Christian religion requires both a real and notional apprehension of the principles contained within the dogmata, real assent being necessary for a relationship with God, and notional assent being necessary for theological thought. He goes on to investigate the operations of the intellect when it makes an act of faith.

Newman explains that to come to a notional apprehension of a personal God is easy (atheists can do it, through intellectual exercise and extrapolation, without giving assent (believing it)). The tougher task is to demonstrate that theists have real apprehension of God, when it is clear that we cannot perceive God by means of our senses. However, this is not the only time the senses have failed to discern what is truly there. Our senses can only perceive phenomenal reality (in the Kantian sense), so we are perceiving the “true substance” of things through our own subjective lens. He uses Kant’s theory of perception, but shows that even if we cannot come to a real apprehension of God through our physical senses, there are other faculties we possess which will allow us to perceive a transcendent God, like our conscience.

These admonitions for actions that are clearly seen to come from outside of our own desires and wishes provide the experience of God to us that allows for real apprehension of Him, and therefore real assent. There is no other mental faculty –aesthetic sense, common sense, etc.—which arouses such fear and guilt as conscience, and this is our internal impression of one facet of God: “Supreme Law-Giver”. This allows for real assent through a real apprehension of this aspect of God (I will let others speak to your ability to de-sensitize your conscience. This is merely an indicator of the kind of apprehension we can have of a personal God). Now we have real assent (remember, assent comes through apprehension).

A Clarification of the Relation of Inference to Assent

The latter portion of Grammar of Assent shifts the focus from the relation of assent to apprehension, to the relation between assent and inference. The Enlightenment thinker views assent as conditional, based on the strength of certainty of the premises, and a conditional conclusion would result in conditional assent, much the way Hume describes his principle of probability. Newman rejects this view because it in no way differentiates assent from inference; he argues that either we need to strike out the term assent from the language of philosophy because it is redundant, or else we need to discern the difference between inference and assent.

Since the characteristic of an inference is that it is conditional, assent must be unconditional. While generally assent follows inference, the two are not indissolubly bound together. Furthermore, since assent is unconditionally given, to assent to a truth necessitates a dismissal of contrary opinions, for if you believe that someone else who disagrees with you may also be correct then you have not truly assented to your proposition; you merely assert it (say it), while still doubting its truth.

The conclusiveness of a proposition is not synonymous with its truth, for something is true objectively, regardless of whether or not it has been proven. While that which is truly disproven cannot be true, it is not false because it was disproven.

We have seen how inference and assent are distinct, but the two are both tied up as a complex action. Christianity addresses minds both through the intellect and through the imagination through arguments too various to list directly, too personal and deep for words, too powerful and concurrent for refutation. Reason is not needed first and faith second (though this is the logical order), but one and the same teaching is in different aspects both object and proof, and elicits one complex act both of inference and of assent.5

The two acts are distinct but must work together in conjunction, for each informs the other. Newman describes this complex interaction as the Illative Sense.6 The illative sense is the collection of all indicators and proofs, logical, experiential, and notional, when looked at as a whole. Through both the notional apprehension of the theological system, and the real apprehension of the presence of God in our hearts (conscience), we can come to truly believe in Him with certainty based in that ‘illative sense.’

Conclusion

The beauty of Newman’s epistemology is that his foundations are the same as those of the philosophers with whom he is engaging. He confronts them using their own terms and language (such as the experiential inferences of Hume and the phenomena of Kant) showing the inconsistency of their own philosophy and proving the integrity of his argument.

Newman sees that liberalism is based on a misunderstanding of assent. Liberal philosophers understand assent as something that we cannot give to religious principles, either because we cannot understand their subject matter or because the propositions are not scientifically demonstrable. Newman shows that assent only requires apprehension, rather than complete “understanding” (that ambiguous term).

Regardless of whether you believe in God or not after reading this (it is not meant to convert), the point is that there is a rational explanation for belief in a personal God. This is not a “proof for God’s existence” as you’ll find elsewhere on the site. It’s an apologia of reasonable faith.

Related Posts

Notes:

- Apologia, 122.

- Newman, John Henry. An Essay in Aid of a Grammar of Assent (London: Longmans, Green, and Co, 1903), 6.

- Grammar, 19.

- Grammar, 20.

- Grammar, 492.

- Ian Ker, Healing the Wound of Humanity, (London: Darton, Longman and Todd, 1993), 8.

Note: Our goal is to cultivate serious and respectful dialogue. While it's OK to disagree—even encouraged!—any snarky, offensive, or off-topic comments will be deleted. Before commenting please read the Commenting Rules and Tips. If you're having trouble commenting, read the Commenting Instructions.