“A Universe from Nothing”

by Dr. Edward Feser

Filed under Book Reviews

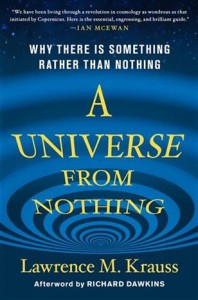

A Universe from Nothing: Why There Is Something Rather than Nothing

by Lawrence M. Krauss

Free Press, 204 pages, 2012

A critic might reasonably question the arguments for a divine first cause of the cosmos. But to ask “What caused God?” misses the whole reason classical philosophers thought his existence necessary in the first place. So when physicist Lawrence Krauss begins his new book by suggesting that to ask “Who created the creator?” suffices to dispatch traditional philosophical theology, we know it isn’t going to end well.

In general, classical philosophical theology argues for the existence of a first cause of the world—a cause that does not merely happen not to have a cause of its own but that (unlike everything else that exists) in principle does not require one. Nothing else can provide an ultimate explanation of the world.

In general, classical philosophical theology argues for the existence of a first cause of the world—a cause that does not merely happen not to have a cause of its own but that (unlike everything else that exists) in principle does not require one. Nothing else can provide an ultimate explanation of the world.

For Aristotle and Thomas Aquinas, for example, things in the world can change only if there is something that changes or actualizes everything else without the need (or indeed even the possibility) of its being actualized itself, precisely because it is already “pure actuality.” Change requires an unchangeable changer or unmovable mover.

For Neoplatonists, everything made up of parts can be explained only by reference to something that combines the parts. Accordingly, the ultimateexplanation of things must be utterly simple and therefore without the need or even the possibility of being assembled into being by something else. Plotinus called this “the One.” For Leibniz, the existence of anything that is in any way contingent can be explained only by its origin in an absolutely necessary being.

But Krauss simply can’t see the “difference between arguing in favor of an eternally existing creator versus an eternally existing universe without one.” The difference, as the reader of Aristotle or Aquinas knows, is that the universe changes while the unmoved mover does not, or, as the Neoplatonist can tell you, that the universe is made up of parts while its source is absolutely one; or, as Leibniz could tell you, that the universe is contingent and God absolutely necessary. There is thus a principled reason for regarding God rather than the universe as the terminus of explanation.

One can sensibly argue that the existence of such a God has not been established. (I think it has been, but that’s a topic for another day.) One cannot sensibly dispute that the unchanging, simple, and necessary God of classical theism, if he exists, would differ from our changing, composite, contingent universe in requiring no cause of his own.

Krauss’ aim is to answer the question “Why is there something rather than nothing?” without resorting to God—and also without bothering to study what previous thinkers of genius have said about the matter. Like Richard Dawkins, Stephen Hawking, Leonard Mlodinow, and Peter Atkins, Krauss evidently thinks that actually knowing something about philosophy and theology is no prerequisite for pontificating on these subjects.

Nor is it merely the traditional theological answer to the question at hand that Krauss does not understand. Krauss doesn’t understand the question itself. There is a lot of farcical chin-pulling in the book over various “possible candidates for nothingness” and “what ‘nothing’ might actually comprise,” along with an earnest insistence that any “definition” of nothingness must ultimately be “based on empirical evidence” and that “‘nothing’ is every bit as physical as ‘something’”—as if “nothingness” were a highly unusual kind of stuff that is more difficult to observe or measure than other things are.

Of course, “nothing” is not any kind of thing in the first place but merely the absence of anything. Consider all the true statements there are about what exists: “Trees exist,” “Quarks exist,” “Smugly ill-informed physicists exist,” and so forth. To ask why there is something rather than nothing is just to ask why it isn’t the case that all of these statements are false. There is nothing terribly mysterious about the question, however controversial the traditional answer.

Read the rest of the review.

Related Posts

Note: Our goal is to cultivate serious and respectful dialogue. While it's OK to disagree—even encouraged!—any snarky, offensive, or off-topic comments will be deleted. Before commenting please read the Commenting Rules and Tips. If you're having trouble commenting, read the Commenting Instructions.