The Stillbirth of Science in Ancient Egypt

by Dr. Stacy Trasancos

Filed under Christianity and Science

NOTE: For the next six Fridays, Strange Notions will present a series of essays by Dr. Stacy Trasancos on the "stillbirths" of science. They're based on Fr. Stanley L. Jaki's research into the theological history of science in the ancient cultures of Egypt, China, India, Babylon, Greece, and Arabia.

The first stillbirth Fr. Stanley L. Jaki discussed in the Savior of Science is the stillbirth of science in Egypt, “an Egypt to be buried in the sand.” In ancient Egypt (from about 3000 B.C.), impressive discoveries and achievements were recorded in history.

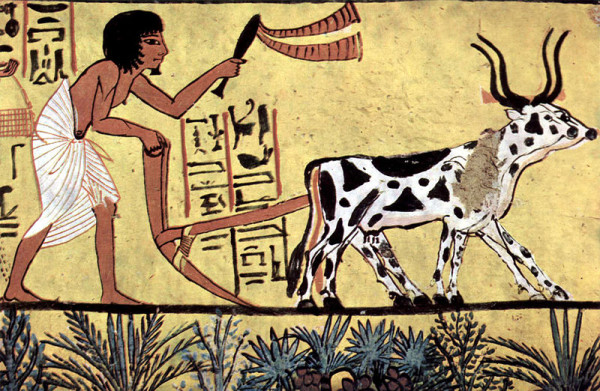

The Egyptians constructed grand pyramids of such majesty and awe that no one today knows how they did it. They invented hieroglyphics, a highly developed form of phonetic writing which may have been the greatest intellectual feat of its kind. They had medical arts. They were successful in using the Nile as an abundant resource. They adopted better weaponry and the use of chariots from other countries. The Egyptian king, Wehimbre Neco, who ruled from 610–595 B.C., sent a fleet to sail West, and the sailors traveled from the Arabian gulf into the southern ocean for three years until they returned to Egypt.

Egyptian social life revolved around practical skill. For the proper distribution of grain and other commodities, ancient Egypt relied on a system of arithmetic in which they took stock of and divided out resources with impressive book-keeping skills. They invented a decimal system with special glyphs for powers of ten up to one million. Their calendar endured uninterrupted use during all of Egyptian history, and the Hellenistic astronomers adopted it for their calculations. Ptolemy based his tables on this calendar in the Almagest on Egyptian years, as did Copernicus to some extent.

Ancient Egyptian craftsmen showed great ingenuity in using their tools. They had a simple but effective method of producing sheets of paper from the leaves of the papyrus plant, much more efficient than the use of animal skin as writing substrates. They were the first to produce plywood as many as six layers deep and made of mixtures of woods. Carpentry among Egyptians used methods of joining wood in intricate patterns for the hulls of boats as well as inlaying, veneering, and overlaying techniques. The burial chambers of Pharaohs of the XVIIIth Dynasty from the sixteenth century B.C. have received much publicity for their highly developed architectural planning containing secret chambers that even space-age technology and sensitive cosmic-ray methods could not detect.

The pyramids, however, constitute the real mystery in Egyptian marvel and ability. Their proportions were enormous. The Egyptian stonecutter placed the huge blocks of stone together with only 1/50 of an inch separation at the base of the pyramid and covered them with marble plates of such smoothness that the pyramids looked like mirrors. They managed to quarry, shape, and polish great stones despite the fact that they had no metal tools. Transportation of the great stones was done with wooden sleds. The overall master plan of the pyramids formed a superbly constructed facility to ensure the king’s journey to the Sun God.

Even with these achievements, the underlying theology and cultural mindset regarding the universe thwarted scientific advancement. “In their deepest meaning the pyramids were symbols of a conception about the world that nipped in the bud all scientific endeavors.” (Science and Creation, 79.) The Egyptians were caught up in an animistic, cyclic outlook that made them insensitive to science as well as history. In their hymns they pictured most parts of the world as animal gods, the whole world itself being one huge animal often depicted as a serpent bent into a circle. In a hymn from ancient texts, the animistic, organismic, rhythmic, and cyclic worldview is explicitly described:

"He [the Indwelling Soul] it was who made the universe in that he copulated with his fist and took the pleasure of emission. I bent right around myself, I was encircled in my coils, one who made a place for himself in the midst of his coils. His utterance was what came forth from his own mouth." (Myths and Symbol in Ancient Egypt, 51.)

The Egyptians believed that the circularity in the sky and in nature was proof that the cosmos was changeless and cyclical too, and that single events or processes had little or no significance, which meant that they “simply could not serve as the carriers of special intellectual content.”

The Egyptians had the talent and the skill to notice that everything in the material world is in motion and is, thus, observable and quantifiable. They had the talent to realize that the scientific method could be applied repeatedly to answer questions about the universe, to determine scientific laws. They had the ability to innovate and the ability to communicate it. They demonstrated the ability to learn from other cultures. Science could have been born in ancient Egypt, but it was not. All of that progress came to a standstill, a stillbirth.

Jaki also pointed out that to argue that “the Egyptians of old failed to develop more science because they did not feel the need for more is an all too transparent form of begging a most serious question,” a conceited psychology (Savior of Science, 23). If they had been but an animal species, they would have never even tried to innovate. They would have continued on their way with things as they were, just as all other animals do. There was plenty of evidence that they did long for something better. During the reign of Akhenaton, the Pharaoh known for abandoning traditional Egyptian polytheism and introducing worship of Aten, a monotheistic deity, Egyptians responded in great number to dispose of long-established rigid art forms and seek “warmly humane representations of life and nature.” Egyptians seemed to want something better. Yet after Akhenaton’s death the traditional religion was restored and Akhenaton became archived as an enemy.

The longing is also evident in the poetry the Egyptians sang, the inspiration they took from the animal kingdom in their carvings of animal and human combined bodies, effigies which now are, as Jaki put it, “buried in the sand as if to symbolize that there was no future in store for the Egypt of old.” (Savior of Science, 25)

In a culture of pantheism, eternity consisted in assimilating to the cyclic motion of nature; souls that reached the stars were considered transfigured spirits absorbed into the great rhythm of the universe. In that context, modern science could have been born, but was not.

Sources:

- Stanley L. Jaki, Science and Creation: From Eternal Cycles to an Oscillating Universe (Edinburgh: Scottish Academic Press, Ltd, 1986), 68-79.

- Stanley L. Jaki, The Savior of Science (Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company), 2000, 22-25.

- Jona Lendering, “The First Circumnavigation of Africa,” Moellerhaus at http://www.moellerhaus.com/Persian/Hist01.html.

- O. Neugebauer, “The Origin of the Egyptian Calendar,” Journal of Near Eastern Studies (1942), 396.

- R. T. Rundle Clark, Myths and Symbol in Ancient Egypt (London: Thames & Hudson, 1959), 51; quoted in Jaki, Science and Creation, 73.

Adapted from the book by Stacy Trasancos, Science Was Born of Christianity: The Teaching of Fr. Stanley L. Jaki (Habitation of Chimham Publishing, 2014), pp. 53-57.

Related Posts

Note: Our goal is to cultivate serious and respectful dialogue. While it's OK to disagree—even encouraged!—any snarky, offensive, or off-topic comments will be deleted. Before commenting please read the Commenting Rules and Tips. If you're having trouble commenting, read the Commenting Instructions.