The Flatlander’s Argument Against Miracles

by Joe Heschmeyer

Filed under Uncategorized

In a Pentecost sermon that was later published as the essay “Transposition,” C.S. Lewis posed a serious objection to the gift of “speaking in tongues,” sometimes called glossolalia. But the objection he makes (as we’ll soon see) applies to everything from miracles to love. First, here’s the dilemma Lewis finds:

The difficulty I feel is this. On the one hand, glossolalia has remained an intermittent “variety of religious experience” down to the present day. Every now and then we hear that in some revivalist meeting one or more of those present has burst into a torrent of what appears to be gibberish. The thing does not seem to be edifying, and all non-Christian opinion would regard it as a kind of hysteria, an involuntary discharge of nervous excitement. A good deal even of Christian opinion would explain most instances of it in exactly the same way; and I must confess that it would be very hard to believe that in all instances of it the Holy Ghost is operating. We suspect, even if we cannot be sure, that it is usually an affair of the nerves. That is one horn of the dilemma.

The other horn of the dilemma is that there’s at least one instance – the original Pentecost (Acts 2) – in which the gift of tongues is described by the authors of Scripture as quite real, and St. Paul makes enough statements in his first letter to the Corinthians that it doesn’t seem to be only a one-time event. So the Christian is not free, as a skeptic is, to say that therefore none of the supposed instances of glossolalia are real. Lewis recognized the apparent weakness of this position:

The sceptic will certainly seize this opportunity to talk to us about Occam’s razor, to accuse us of multiplying hypotheses. If most instances of glossolalia are covered by hysteria, is it not (he will ask) extremely probable that that explanation covers the remaining instances too?

Another way of formulating this objection would be like this: you say that A is spiritual and B isn’t, but A and B look identical. The point here is much bigger than speaking in tongues. Speaking in tongues looks like nervous energy. But it is also true that the miraculous healing often looks like the natural healing. The couple in love and the couple in lust may look the same. And indeed, even thinking looks like it’s just atoms moving around in the brain! So why believe in miracles, or in romantic love, or in thought? Lewis points out that this leads us to the absurd conclusion that we have to reject truth and falsity:

We are certain that, in this life at any rate, thought is intimately connected with the brain. The theory that thought therefore is merely a movement in the brain is, in my opinion, nonsense; for if so, that theory itself would be merely a movement, an event among atoms, which may have speed and direction but of which it would be meaningless to use the words “true” or “false”.

Atoms move in the brain when you think, but that doesn’t mean that “atoms moving in my brain” and “I think a thought” are the same thing. Expressing a thought in writing moves ink onto the page, but that doesn’t mean that there’s no difference between an ink spill and a letter. Likewise, to reduce “thinking” to a certain set of atomic movements within the brain renders any talk of a thought being “true” or “false” nonsensical (how could any one movement of atoms be any more or less “true” than any other?). And indeed, Lewis notes that on a merely physical level, even extreme joy and anguish look the same – the tightening in the chest, the racing of the heart, and so on. He concludes that “if I were to judge simply by sensations I should come to the absurd conclusion that joy and anguish are the same thing, that what I most dread is the same with what I most desire.”

So there seems to be something obviously wrong with the skeptic’s objection. But there’s still something confusing: why is it that supernatural things look like natural things, if they are (in reality) different? Lewis points out that we would expect them to look much the same, because it’s a richer system (spiritual phenomena) being expressed in the limited language of the body. He calls this theory “correspondence” or “transposition.” And we find it anytime you try to express something in a richer language in a more limited one. For instance, spoken English has something like 19 and 22 distinct vowel sounds. But written English only has A, E, I, O, and U (and sometimes Y or W). And so there’s a limitation, which is how you end up with “take a bow” and “violin bow,” or the bizarre case of “boy,” “cow,” “lot,” and “toe,” in which the “o” is pronounced differently each time. But Lewis gives another example that might be clearer:

The most familiar example of all is the art of drawing. The problem here is to represent a three-dimensional world on a flat sheet of paper. The solution is perspective, and perspective means that we must give more than one value to a two-dimensional shape. Thus in a drawing of a cube we use an acute angle to represent what is a right angle in the real world. But elsewhere an acute angle on the paper may represent what was already an acute angle in the real world: for example, the point of a spear on the gable of a house. The very same shape which you must draw to give the illusion of a straight road receding from the spectator is also the shape you draw for a dunces’ cap.

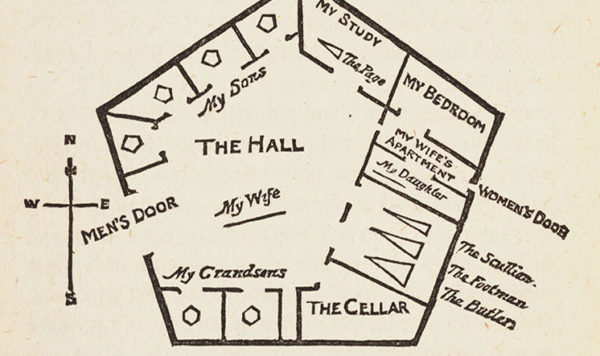

Because you’ve seen houses in real life, you can tell where the artist means the slanted lines to represent that one thing is higher than another, or whether it simply means that one thing is further away. But imagine a “Flatlander,” who only knew the world of drawings, and you can see where skepticism might come in:

If we can imagine a creature who perceived only two dimensions and yet could somehow be aware of the lines as he crawled over them on the paper, we shall easily see how impossible it would be for him to understand. At first he might be prepared to accept on authority our assurance that there was a world in three dimensions. But when we pointed to the lines on the paper and tried to explain, say, that “This is a road,” would he not reply that the shape which we were asking him to accept as a revelation of our mysterious other world was the very same shape which, on our own showing, elsewhere meant nothing but a triangle. And soon, I think, he would say, “You keep on telling me of this other world and its unimaginable shapes which you call solid. But isn’t it very suspicious that all the shapes which you offer me as images or reflections of the solid ones turn out on inspection to be simply the old two-dimensional shapes of my own world as I have always known it? Is it not obvious that your vaunted other world, so far from being the archetype, is a dream which borrows all its elements from this one?”

Lewis calls this perspective the “view from below.” If all you know of English is written English, you’re going to be skeptical and confused when someone tells you about the myriad sounds than an “o” can make. If you’ve never seen life in 3-D, it’s going to be nearly impossible to understand what’s going on in a drawing of a house. And if you know nothing of the spiritual life, and think that there’s nothing outside of chemicals and animal passions and swirling atoms, you lack the framework to make any sense of higher phenomena, like miracles, or even love or thought. Lewis’ point is that this skepticism is both perfectly reasonable and completely wrong. But it’s wrong because there’s more evidence that the skeptic doesn’t see, or perhaps doesn’t even have:

The sceptic’s conclusion that the so-called spiritual is really derived from the natural, that it is a mirage or projection or imaginary extension of the natural, is also exactly what we should expect; for, as we have seen, this is the mistake which an observer who knew only the lower medium would be bound to make in every case of Transposition. The brutal man never can by analysis find anything but lust in love; the Flatlander never can find anything but flat shapes in a picture; physiology never can find anything in thought except twitchings of the grey matter. It is no good browbeating the critic who approaches a Transposition from below. On the evidence available to him his conclusion is the only one possible.

The solution, in each of these cases, is to approach the question instead “from above.” From that perspective, it’s clear how love and lust can differ so dramatically, even if some of the same external actions are involved in both; it’s likewise clear how thinking differs from the mere sloshing around of parts of the brain; and it’s clear how God can intervene in the order of nature in a way distinct from the ordinary course of events, or how the Holy Spirit can give particular charisms to people… even if each of these things looks virtually indistinguishable from its “lower” cousin on an external level.

Two men might appear to be identical, if you look only at the shape of their shoes. And from that perspective, they may in fact be indistinguishable. But that doesn’t actually mean that they’re the same. It just means that you need to approach things from a different angle… from higher up.

Now, Lewis’ argument doesn’t prove that the view from above is therefore right. Certainly, it’s likely to sound absurd to a Flatlander or a brute, who views everything from below. Nor does it mean that every purported miracle or supernatural gift is authentic, or that everyone with a furrowed brow is deep in thought, or that every declaration of love is the real deal. Instead, it’s simply to say that the Flatlander’s objective, which sounded so persuasive at first, is really just a reflection of his own limited perspective, and that if we’re ever going to have any luck telling what’s real or what isn’t, we’re going to have to approach it with the “view from above.”

Related Posts

Note: Our goal is to cultivate serious and respectful dialogue. While it's OK to disagree—even encouraged!—any snarky, offensive, or off-topic comments will be deleted. Before commenting please read the Commenting Rules and Tips. If you're having trouble commenting, read the Commenting Instructions.