The Deflation of Inflationary Theory

by Dr. Benjamin Wiker

Filed under Cosmology

If you study the history of science long enough, you realize that you've got to ask two questions about any scientific theory, especially the biggest and most grand of them. What is it? Why was it put forth? The two almost invariably go together. We cannot truly grasp what the theory is, until we understand the motives of those who developed it.

Now here the obvious objection would be this. The what of a theory is really the only question, because the why is so obvious as not to need asking. The motive of every scientist is to discover the truth about reality. He puts forth his theory because he wants to get at what things really are, and he believes that his theory helps to explain current perplexities, unify disparate data, and provide a theoretical framework for future fruitful research and discovery.

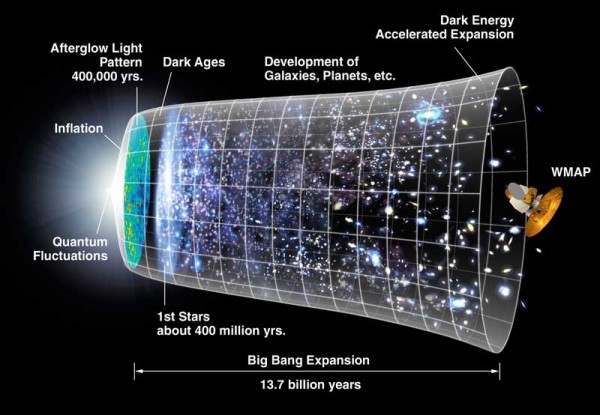

Certainly the what is sufficient in many cases, but not all. Consider the current rage for Multiverse Theory. In this case, they why almost entirely explains the what. Before the Big Bang, almost all scientists believed that the universe was eternal. Eternal universes don't need a God to create them. It looked like science supported atheism. So when scientists discovered the Big Bang—that the universe had a definite beginning, and quite literally came into being out of nothing—they recoiled and rebelled. Suddenly, it looked as if the theistic account had trumped the scientists' efforts to explain the universe without God.

Even worse, from the secular perspective, was that the more scientists dug into the beginning of things, the more they discovered that the universe from its birth to its present state is astoundingly fine-tuned, so finely-tuned, so delicately balanced, so excruciatingly calibrated in every aspect that one could only reasonably conclude (to quote physicist Fred Hoyle's famous words) that "a super intellect has monkeyed with physics, as well as chemistry and biology, and that there are no blind forces worth speaking about in nature."

Multiverse Theory appears to be a desperate response to this situation. Exquisite fine-tuning is a scientific fact. The only way around it for the secular-minded was to suggest that there are actually an infinite number of other universes, and that we just happened to be one of the lucky few that by mere chance turned out so nicely. The cosmic lottery approach has, however, a few serious drawbacks:

- There is no evidence for it.

- There is no way to get evidence for it.

- The only reason that it exists as a theory is that certain scientists do not like the theistic implications of the Big Bang and fine-tuning.

So here, the what is entirely explained in terms of the why, or the motives of those that put forth Multiverse Theory.

Now what about Inflationary Theory? First of all, unlike Multiverse Theory, Inflationary Theory is actually in textbooks as if it were a fact, an elegant implication of Big Bang cosmology that all reasonable scientists accept. And second, unlike Multiverse Theory, which doesn't explain anything, Inflationary Theory has at least born some fruit. It does seem to explain some things, and appears to have helped scientists to make theoretical headway in sorting out the complexities of our cosmos. That's why it got into textbooks as a theory that's all but a fact. Or so it seems.

But things aren't always what they seem. In a recent Scientific American (April 2011), one of the architects of Inflationary Theory, Paul Steinhardt, makes some startling admissions both about the caliber of the theory itself, and even more, about the motives in putting it forth.

As it turns out, Inflationary Theory shares this, at least, with Multiverse Theory: it was put forth to avoid a fine-tuning "problem," the so-called "flatness problem." Space isn't a big, pre-existing blackboard into which the Big Bang pops into existence; space itself came into being with the Big Bang, and its "shape" or curvature is directly affected by the density of matter and energy in it. Too much, and you get what's called a "closed" universe, which instead of expanding in a nicely uniform way, collapses back in upon itself. Too little, and you've got an "open" universe, and expansion yields cosmic smithereens. But with just the right density, the exact, very precise amount teetering on a razor's edge between too much and too little, you get, well, our universe, a "flat" universe.

Inflationary Theory was put forth, in great part, to solve that "problem," a problem that is only a problem if you refuse to infer the reasonable conclusion that the creation of our universe was too profoundly well-orchestrated for it to be put down to a cosmic accident. Inflationary theorists tried to get around the God problem by assuming that all that was needed was a fantastic growth spurt right at the very beginning of the Big Bang that ironed out all the wrinkles so to speak, and ensured that the universe would be, as it is, remarkably uniform, with only a very, very few tiny variations in the distribution of matter and energy. If inflation could be assumed, then unseemly "globs" of energy that would unbalance and warp expansion could be, as it were, mixed thoroughly into the batter through an initial burst of rapid expansion. (Inflation also helps to explain the "horizon problem," the fact that parts of the universe that could not possibly be connected causally, have a uniform temperature—but again, that's a problem only if you want the Big Bang to be a cosmic accident.)

Now comes a confession by Paul Steinhardt, who helped put the whole Inflationary model together. "Something peculiar has happened to inflationary theory" since its inception about three decades ago. "As the case for inflation has grown stronger, so has the case against [it]. The two cases are not equally well known: the evidence favoring inflation is familiar to a broad range of physicists, astrophysicists and science aficionados. Surprisingly few seem to follow the case against inflation….Most astrophysicists have gone about their business testing the predictions of textbook inflationary theory without worrying about these deeper issues, hoping they would eventually be resolved. Unfortunately, the problems have resisted our best efforts to date."

What are the problems? First, in order for inflation to produce the universe we actually live in, the inflation energy itself would have to have been very precisely tuned. Second, the initial conditions had to be exactly right as well: "Of all the ways the universe could have begun, only a tiny fraction would lead to the uniform, flat state observed today." Third, there is nothing about inflation that stops it. Inflation is eternal, and therefore ends up creating an infinity of universes of every variety, not just our just-so universe. The upshot: the theory can make no exact predictions that would explain our universe. "What does it mean to say that inflation makes certain predictions," laments Steinhardt, "if anything that can happen will happen an infinite number of times. And if the theory does not make testable predictions, how can cosmologists claim that the theory agrees with observations, as they routinely do?" The only way around this last problem is to have the inflation energy and initial conditions finely-tuned so as to achieve the actual outcome: our delicately balanced, wonderfully wrought universe.

Does that spell the end of Inflation as a theory? No, because a majority of scientists continue to give it their support, they will undoubtedly continue to chip away at the "problem" of fine-tuning. It is, for the secular-minded scientist, very difficult to admit that they are still bewildered with fine-tuning after thinking they had a way around at least some of it with Inflation.

Does that bring Steinhardt back to accepting the fact that the universe is finely-tuned? No, he's since come up with a rival theory to Inflation, "Cyclic Theory." The problem with cyclic theory—which isn't really new—is that it pushes back the same questions about fine-tuning to a "previous" universe that expanded and contracted and produced this one.

As critics have noted, Cyclic Theory creates more problems than it solves. It may soon follow the fate of Inflationary Theory. But because it doesn't involve God, it still has traction today among scientists who will take seriously any explanation of the universe, so long as it doesn't involve God.

Related Posts

Note: Our goal is to cultivate serious and respectful dialogue. While it's OK to disagree—even encouraged!—any snarky, offensive, or off-topic comments will be deleted. Before commenting please read the Commenting Rules and Tips. If you're having trouble commenting, read the Commenting Instructions.