Is Religion Just a Social Construct?

by Joe Heschmeyer

Filed under Religion

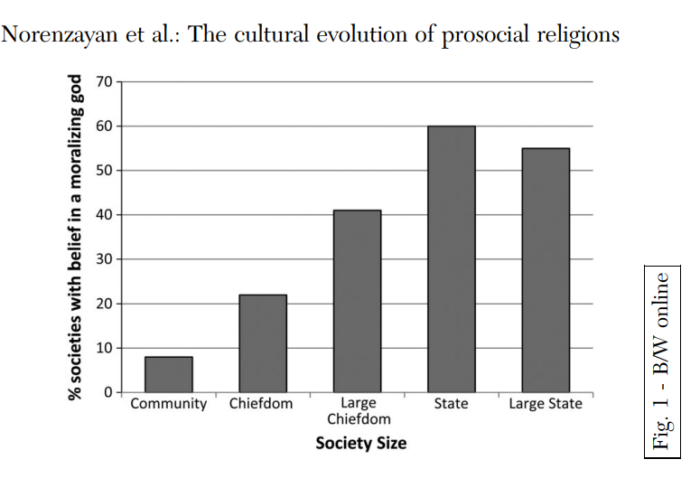

One of the arguments against religion is that it’s a social construction – that is, that religion (particularly, belief in an interventionist or “moralistic” god, meaning a god interested in human affairs and morality) is something invented by society, in order to regulate its citizenry. One of the best arguments in favor of this is that more developed societies have more developed religious systems, and are more likely to believe in a god who cares about morality:

This has led to a chicken-and-egg question: does a “pro-social” religion (that is, a religion whose morality is conducive towards healthy social conduct) help to cause the rise of complex societies, or does the rise of such a state help to cause the rise of pro-social religion?

As PBS notes, dozens of studies throughout the 2000s pointed to the former answer: moral religion seems to have come first, and complex society followed. But a new study, published in Nature, argues the opposite: that complex societies precede moralizing gods throughout world history. In other words, only once a society hits about a population of about 1 million do we see widespread belief in a god interested in moral questions.

This result is much ballyhooed, because it seems to suggest that moral religion is just a social construct – the State (or at least social forces) need to police their people, and so they start saying “God doesn’t want you to misbehave,” and boom, moral religion is born. But there are a few problems:

- The Nature article is extremely premature. Joe Henrich, chair of Harvard University’s Department of Human Evolutionary Biology, said “These guys were a little bit quick on the draw with putting this paper out because the data is largely not checked.” That’s a diplomatic way of putting it. The claims behind the Nature study require careful historical examination of thousands of ancient texts to determine age and whether or not the text implies moral religion. As PBS notes, actually doing that research carefully will take years.

- Forward bias. There’s a related problem with dating. Let’s say you find a manuscript from the 4th century. Does that mean that it’s the version handwritten by the original author? Frequently, what we have are copies of copies – whatever happened to have been written on a reliable material (like papyrus) and stored in the right climate (like a cave in Egypt, where it won’t be impacted by the elements). The vast majority of what human beings have written throughout history has probably been destroyed. Back in 2012, a small Greek fragment was discovered of St. Justin Martyr’s First Apology. Justin Martyr wrote his text between A.D. 155-157. The scrap that was discovered dates to the 300s. But here’s the crucial thing: until that point, the oldest copy we had of that document was from more than a thousand years later. Why does that matter? Because the society-came-first hypothesis falls completely apart if it turns out that moral religion is older than the fragments we have.

- The anti-religion conclusions don’t follow. Let’s say that it’s true that moral religion doesn’t really spread until a society’s population hits a million people or so. (Again, it’s quite premature for that, but let’s assume for the sake of argument). Does it follow that religion is just a social construct? Not at all. Think about it this way: science doesn’t really take off until society hits a certain point of complexity, advancement, and stability. When a society is spending its time avoiding getting eaten by tigers, they’re not pondering the Big Questions of life, or at least, they’re not taking the time to write those down and preserve them. So (despite the ballyhoo) very little about the truth or falsity of religion or science can be proven from the dating question.

To look at it from another angle, as communities develop, they’re more likely to believe in a moral god… but that’s only true to a certain point. Extremely large societies actually get a little less religious. So one could just as easily argue that irreligion is a “social construct” (or deconstruction) for particularly powerful countries. And it’s easy to come up with theories about this: powerful empires want single-minded obedience to the state and political rulers, not to the gods or religious leaders. But notice that these are just ways of impugning peoples’ motives for belief or disbelief – they tell us preciously little about the question that really matters… whether or not religion is TRUE.

The closest we get to that, at least in the PBS article, comes from the anthropologist Peter Peregrine, who says “There are no societies that are a-religious. Belief in the supernatural, in a spiritual world is a fundamental human feature. It’s part of the human condition.” This creates a real pickle for atheists. If you try to explain away this innate belief structure evolutionarily, that our minds believe a falsehood like religion because it’s beneficial for group survival, you’re undermining the reliability of the mind. In other words, if you’re using your mind to say that your mind is hardwired to believe convenient fictions, is there any reason to believe that religion is the fiction, and not your waving it away?

Fr. (now Bishop) Robert Barron points out a fascinating argument that Pope Benedict XVI made, pointing in this same direction:

Ratzinger commences with the observation that finite being, as we experience it, is marked, through and through, by intelligibility, that it is to say, by a formal structure that makes it understandable to an inquiring mind. In point of fact, all of the sciences – physics, chemistry, psychology, astronomy, biology, and so forth – rest on the assumption that at all levels, microscopic and macroscopic, being can be known. The same principle was acknowledged in ancient times by Pythagoras, who said that all existing things correspond in numeric value, and in medieval times by the scholastic philosophers who formulated the dictum omne ens est scibile (all being in knowable).

Ratzinger argues that the only finally satisfying explanation for this universal objective intelligibility is a great Intelligence who has thought the universe into being. Our language provides an intriguing clue in this regard, for we speak of our acks of knowledge as moments of “recognition,” literally a re-cognition, a thinking again what has already been thought. Ratzinger cites Einstein in support of this connection: “in the laws of nature, a mind so superior is revealed that in comparison, our minds are as something worthless.” The prologue to the Gospel of John states, “In the beginning was the Word,” and specifies that all things came to be through this divine Logos, implying thereby that the being of the universe is not dumbly there, but rather intelligently there, imbued by a creative mind with intelligible structure.

In other words, all science presupposes that the universe is intelligible and that our minds are sufficiently reliable that we can make sense of this intelligibility. The universe has a “language” all its own (which points to a Creator) and our minds are capable of speaking this language (which also points to a Creator). To reject the mind as unreliable doesn’t just undermine religion – it undermines all science and all knowledge, which ends up being self-refuting.

So you are left with either saying that the mind is reliable, which means we should listen to its religious impulse, or the mind is unreliable, in which case how are you sure you should trust anything (your senses, your belief in science, your rejection of religion, or even your belief that the mind is unreliable, etc.?).

Related Posts

Note: Our goal is to cultivate serious and respectful dialogue. While it's OK to disagree—even encouraged!—any snarky, offensive, or off-topic comments will be deleted. Before commenting please read the Commenting Rules and Tips. If you're having trouble commenting, read the Commenting Instructions.