How to Perfectly Know the Existence of God

by Joe Heschmeyer

Filed under The Existence of God

It's common today to hear both believers and nonbelievers claim that the existence of God is ultimately unknowable, or at least unprovable. According to this view, we're left to take a leap of faith, or else to go with the option we think is more likely.

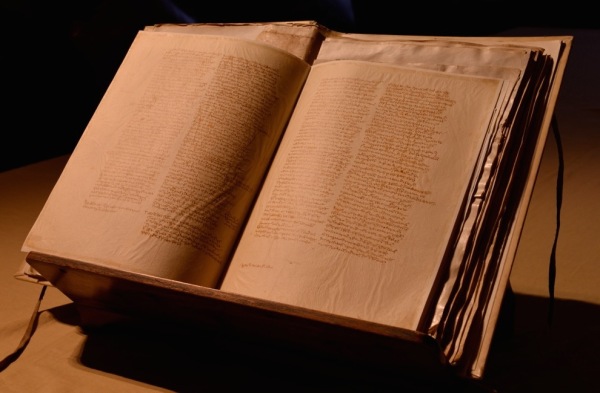

Classical theism rejects this idea completely. It claims to be able to prove the existence of God - to be able to prove, in fact, that He can't not exist. And what's amazing is that these theists seem capable of following through on this promise. There are several of these non-probabilistic arguments for the existence of God, but one of the strongest (and most misunderstood) is the argument from contingency. This is presented in St. Thomas Aquinas' Five Ways in the Summa Theologiae, although Aquinas actually gives a better version of the same argument in the Summa Contra Gentiles.

To see how the argument works, let's define two of our terms, and then lay out the two syllogisms that get us to a sure knowledge of the existence of God.

What Do We Mean by “Contingent” and “Necessary”?

For this argument to make sense, we need to define a few terms; namely:

- Contingent beings are those being that only exist under particular conditions. They don't have to exist, and they don't always exist. Rather, they come into existence under particular conditions, and require certain conditions to continue to exist. Humanity, for example, requires air, water, carbon, and a whole host of other things. If any of these variables ceased to exist, so would we. In other words, contingent beings are things that could not-be. They exist, but only because certain conditions are met.

- Necessary beings are the opposite. They exist necessarily. Or, if you'll excuse the double negative, necessary beings couldn't not-be. If there were some set of circumstances in which these beings could cease to exist, then their existence would be contingent, and they'd be up there in the first group. This means that necessary beings aren't capable of generation or corruption (that is, of being born or dying).

With that in mind, let's consider the two arguments that bring us to a sure knowledge of the existence of God:

Argument I: Something Necessary Exists

Step 1: We see in the world some things that can be and not-be.

In other words, we see contingent things all around us. We see birth and death, both in the literal sense for organic matter, and in the metaphorical sense: we see galaxies come into, and go out of existence, for example.

This should raise a question for us: Why is there something, rather than nothing? After all, seemingly everything we see could not-be. Keep that question in mind.

Step 2: Everything contingent has some other cause for its being.

Under particular circumstances, a tree will exist. But if those conditions aren't there, the tree will never come into existence; or, if it already exists, it'll go out of existence. So, for example, if the soil temperature suddenly increased a thousand degrees, your tree would quickly blink out of existence. But this means that the tree isn't the cause of its own being. If it were, it could never not-be, and would exist necessarily, not contingently.

And of course, this point isn't limited to trees. It's true of every contingent being, including you and I, the cosmos, etc. So if you say that X is a contingent being, then some conditions (Y) must exist for X to exist.

Step 3: This can't go on infinitely.

If X requires Y to exist, and Y requires Z to exist, you can't just draw that chain out infinitely. At some point, you must arrive at something that does exist, and isn't dependent upon something else for its existence.

Another way to approach this question: what conditions are necessary for you to exist right now? We're talking about the kind of conditions that you literally can't live without, here and now. And there can't be an infinite number of them, or you (and everything else) wouldn't exist.

The branch you're sitting on may be connected to another branch, but at some point, it needs to meet up with something grounded, like a trunk. You can't just have an infinite chain of branches dangling in the air. If literally everything is contingent, there's nothing capable of bringing it from non-existence into existence, or keeping it in existence.

Conclusion: There must be something necessary.

If there's nothing necessary, you end up with the logically-impossible infinite regress described in step 3. So there must be something that can't not exist.

Shrewd atheists will sometimes object at this point that this doesn't prove God. They're right; at this point, we've just shown that at least one thing can't not exist. That could be God, or gods, or angels, or a Demiurge, or matter, or mathematical laws... or more than one of these things.

So we haven't proven monotheism yet. But we've still made some headway: many of the popular atheistic cosmologies actually fail to clear this first hurdle: they assume a universe in which everything comes about under the right conditions, but don't have anyway of accounting for those conditions (or hold that those conditions require other conditions, and so on...).

To get from “something necessary” to “God” requires a second line of argumentation.

Argument II: God Exists

Step 1: Every necessary being either (a) has its necessity caused by something outside of itself, or (b) doesn't.

As Aquinas put it, “every necessary thing either has its necessity caused by another, or not.”

What does this mean? Well, imagine a universe in which there were seven eternal angels. Incapable of being born or dying, they're in the category of necessary beings. But we're still left asking, why do these angels exist? The fact that they can't be born or die doesn't finish our inquiry, because it doesn't give an account of their existence. There could just as easily be a universe with a thousand such angels, or none.

So the necessity of these angels is caused by something else: some external cause must exist to account for their timeless existence. They're in category (a).

Step 2: If all necessary beings were in category (a), you would have an infinite regress.

This is a parallel line of argumentation to what we saw in steps 2-3 of Argument I. If everything depends on something else for its existence, how does anything exist?

Step 3: Therefore, not every necessary being has its existence from another. A necessary being exists who has its necessity through itself and so is the cause of the necessary being of any other necessary thing – which being all call “God.”

Let's unpack those conclusions, one by one:

- A necessary being exists who has its necessity through itself: In other words, Something not dependent upon anything at all to exist. This Something literally can't not exist, in this or any possible universe. (If its existence was contingent upon a particular type of universe, we'd be right back in the infinite regress problems detailed above).

- A necessary being who is the cause of all other necessary (and contingent!) things: Everything else we've talked about—you and me and all contingent realities, as well as all the necessary realities in category (a)—depends, either directly or indirectly, on this Something to exist. In other words, if this Something didn't exist, everything would instantly blink out of existence.

- This Something is Unlimited Being: This is implicit, but I wanted to draw it out explicitly. When we're talking about Something that exists necessarily, and isn't determined by anything else, we're talking about Something whose being is necessarily limitless. (If its being were limited by some external cause, where does that cause come from?)

- This Something is what we call “God”: For those used to thinking of God as a created being, perhaps this seems like a big jump. But we've arrived at the existence of a Something that exists by definition, and exists as “pure Being” or “unlimited Being.” And that's the best definition of God, and the definition of God that He gives (see below).

What's brilliant about this is that we're not left with a probabilistic argument for God. We're not left saying, for example, “given how complex the universe is, it's 99% likely that it was designed by a deity” or something. Rather, we've concluded to a God that must exist, who literally can't not exist. And this conclusion both establishes God's existence, and starts to tell us something about Him.

Of course, it's important to realize the limitations of our approach. Necessarily, we're limiting ourselves to what we can know by reason alone. After all, it would be terribly circular to argue that God exists because the Bible says He does, and we can trust the Bible because God inspired it, etc.

That restriction really is a handicap, because certain things about God can only be known by revelation. For example, you could never arrive at the Trinity from reason alone. Indeed, if everything about God could be known fully by reason alone, there would hardly be any reason for revelation. So unaided reason gets us to the doorway, to see that there is a God. To find out more about this God, we need to let Him introduce Himself.

And quite fascinatingly, when He does so, in Exodus 3:14, it's as YHWH, “I AM WHO AM.” In other words, what we see in revelation corresponds perfectly to what we concluded to by reason alone: a God who exists by definition, and whose existence accounts for the existence of everything else in the universe.

Related Posts

Note: Our goal is to cultivate serious and respectful dialogue. While it's OK to disagree—even encouraged!—any snarky, offensive, or off-topic comments will be deleted. Before commenting please read the Commenting Rules and Tips. If you're having trouble commenting, read the Commenting Instructions.