How Christians—Not the “Enlightenment”—Launched the Age of Reason

by Brandon Vogt

Filed under History

As we all know, and as many of our well established textbooks have argued for decades, the Dark Ages were a stunting of intellectual progress to be redeemed only by the secular spirit of the Enlightenment. The Inquisition was one of the most frightening and bloody chapters in Western history; the religious Crusades were an early example of religious thirst for riches and power; and Pope Pius XII was anti-Semitic and rightfully called “Hitler’s Pope.”

But what if these long held beliefs were all wrong?

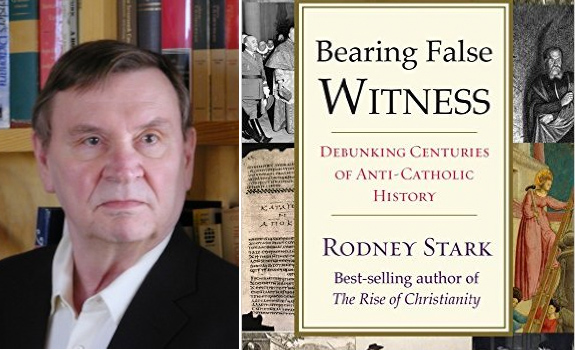

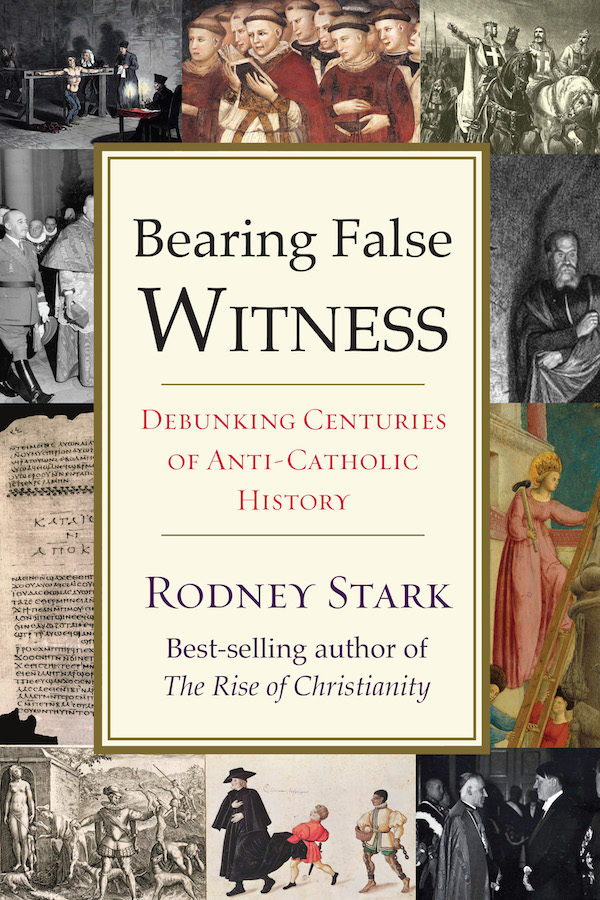

That's what Dr. Rodney Stark argues in his latest and much-discussed book, Bearing False Witness: Debunking Centuries of Anti-Catholic History (Templeton Press, 2016). The book is not a Catholic attempt to rewrite history in the Church's favor. In fact notably, Stark isn't even Catholic himself. The accomplished sociologist and past president of the Society for the Scientific Study of Religion has long identified as an agnostic, though today calls himself an "independent Christian." That makes his book less a work of religious apologetics and more historical remediation. He wants to correct myths and get at the truth.

Specifically, his new book addresses ten prevalent anti-Catholic myths. These include:

- Instead of the Spanish Inquisition being an anomaly of torture and murder of innocent people persecuted for “imaginary” crimes such as witchcraft and blasphemy, Stark argues that not only did the Spanish Inquisition spill very little blood, but it was a major force in support of moderation and justice.

- Instead of Pope Pius XII being apathetic or even helpful to the Nazi movement, such as to merit the title, “Hitler’s Pope,” Stark shows that the campaign to link Pope Pius XII to Hitler was initiated by the Soviet Union, presumably in hopes of neutralizing the Vatican in post-World War II affairs. Pope Pius XII was widely praised for his vigorous and devoted efforts to saving Jewish lives during the war.

- Instead of the Dark Ages being understood as a millennium of ignorance and backwardness inspired by the Catholic Church’s power, Stark argues that the whole notion of the “Dark Ages” was an act of pride perpetuated by anti-religious intellectuals who were determined to claim that theirs was the era of “Enlightenment.”

Today at Strange Notions, we feature an excerpt from the book dealing with that last myth. Enjoy the excerpt, and be sure to pick up your copy of the book today!

The single most remarkable and ironic thing about the “Enlightenment,” is that those who proclaimed it made little or no contribution to the accomplishments they hailed as a revolution in human knowledge, while those responsible for these advances stressed the continuity with the past. That is, Voltaire, Rousseau, Diderot, Hume, Gibbon and the rest were literary men, while the primary revolution they hailed as the “Enlightenment” was scientific. Equally misleading is the fact that although the literary men who proclaimed the “Enlightenment” were irreligious, the central figures in the scientific achievements of the era were deeply religious, and as many of them were Catholics as were Protestants.1 So much then for the idea that suddenly in the sixteenth century, enlightened secular forces burst the chains of Catholic thought and set the foundation for modern times. What the proponents of “Enlightenment” actually initiated was the tradition of angry secular attacks on religion in the name of science − attacks like those of their modern counterparts such as Carl Sagan, Daniel Dennett, and Richard Dawkins. Presented as the latest word in sophistication, rationalism, and reason, these assaults are remarkably naïve and simplistic − both then and now.2 In truth, the rise of science was inseparable from Christian theology, for the latter gave direction and confidence to the former (Chapter 7).

Theology, Reason, and Progress

Claims concerning the revolutionary character of the “Renaissance” and the “Enlightenment” were plausible because remarkable progress was made in these eras. But rather than being a revolutionary break with the past, these achievements were simply an extension of the accelerating curve of progress that began soon after the fall of Rome. Thus, the historian’s task is not to explain why so much progress has been made since the fifteenth century−that focus is much too late. The fundamental question about the rise of the West is: What enabled Europeans to begin and maintain the extraordinary and enduring period of rapid progress that enabled them, by the end of the “Dark Ages,” to have far surpassed the rest of the world? Why was it that, although many civilizations have pursued alchemy, it led to chemistry only in Europe? Or, while many societies have made excellent observations of the heavens and have created sophisticated systems of astrology, why was this transformed into scientific astronomy only in Europe?

Several recent authors have discovered the secret to Western success in geography. But, that same geography long sustained European cultures that were well behind those of Asia. Others have traced the rise of the West to steel, or to guns and sailing ships, and still others have credited a more productive agriculture. The trouble is that these answers are part of what needs to be explained: Why did Europeans excel at metallurgy, ship-building, or farming?. I have devoted a book to my answer: that the truly fundamental basis for the rise of the West was an extraordinary faith in reason and progress, and this faith originated in Christianity.3

Several recent authors have discovered the secret to Western success in geography. But, that same geography long sustained European cultures that were well behind those of Asia. Others have traced the rise of the West to steel, or to guns and sailing ships, and still others have credited a more productive agriculture. The trouble is that these answers are part of what needs to be explained: Why did Europeans excel at metallurgy, ship-building, or farming?. I have devoted a book to my answer: that the truly fundamental basis for the rise of the West was an extraordinary faith in reason and progress, and this faith originated in Christianity.3

It has been conventional to date the “Age of Reason” as having begun in the seventeenth century. In truth, it really began late in the second century, launched by early Christian theologians. Sometimes described as “the science of faith,”4 theology consists of formal reasoning about God. The emphasis is on discovering God’s nature, intentions, and demands, and on understanding how these define the relationship between human beings and God. And Christian thinkers have done this, not through meditation, not through new revelations, not through inspiration, but through reason.

Indeed, it was not unusual for Christian theologians to reason their way to a new doctrine; from earliest days Christian thinkers celebrated reason as the means to gain greater insight into divine intentions. As Quintus Tertullian (155-239) instructed in the second century: "reason is a thing of God, inasmuch as there is nothing which God the Maker of all has not provided, disposed, ordained by reason—nothing which He has not willed should be handled and understood by reason."5 In the same spirit, Clement of Alexandria (150-215) warned: “Do not think that we say that these things are only to be received by faith, but also that they are to be asserted by reason. For indeed it is not safe to commit these things to bare faith without reason, since assuredly truth cannot be without reason.”6

Hence, Augustine (354-430) merely expressed the prevailing wisdom when he held that reason was indispensable to faith: "Heaven forbid that God should hate in us that by which he made us superior to the animals! Heaven forbid that we should believe in such a way as not to accept or seek reasons, since we could not even believe if we did not possess rational souls." Augustine acknowledged that "faith must precede reason and purify the heart and make it fit to receive and endure the great light of reason." Then he added that although it is necessary "for faith to precede reason in certain matters of great moment that cannot yet be grasped, surely the very small portion of reason that persuades us of this must precede faith."7 Christian theologians always have placed far greater faith in reason than most secular philosophers are willing to do today.8

In addition, from very early days, Catholic theologians have assumed that the application of reason can yield an increasingly more accurate understanding of God's will. Augustine noted that although there were "certain matters pertaining to the doctrine of salvation that we cannot yet grasp...one day we shall be able to do so."9 This universal faith in progress among Catholic theologians had immense impact on secular society as well. Thus, Augustine celebrated not only theological progress, but earthly, material progress as well. Writing early in the fifth century, he exclaimed: "has not the genius of man invented and applied countless astonishing arts, partly the result of necessity, partly the result of exuberant invention, so that this vigour of mind...betokens an inexhaustible wealth in the nature which can invent, learn, or employ such arts. What wonderful—one might say stupefying—advances has human industry made in the arts of weaving and building, of agriculture and navigation!" He went on to admire the "skill [that] has been attained in measures and numbers! With what sagacity have the movements and connections of the stars been discovered!" and all of this was due to the "unspeakable boon" that God conferred upon his creation, a "rational nature."10

Augustine's optimism was typical among medieval intellectuals; progress beckoned. As Gilbert de Tournai wrote in the thirteenth century, "Never will we find truth if we content ourselves with what is already known...Those things that have been written before us are not laws but guides. The truth is open to all, for it is not yet totally possessed."11 Especially typical were the words preached by Fra Giordano in Florence in 1306, "Not all the arts have been found; we shall never see and end to finding them. Every day one could discover a new art."12 Compare this with the prevailing view in China at this same time, well-expressed by Li Yen-chang, "If scholars are made to concentrate their attention solely on the classics and are prevented from slipping into study of the vulgar practices of later generations, then the empire will be fortunate indeed!"13

It is a widely believed, even by very secular scholars, that the ‘idea of progress’ was crucial to the rise of Western Civilization.14 Because Europeans believed progress was possible, desirable, and to some extent inevitable, they eagerly pursued new methods, ideas, and technologies. As it turned out, these efforts were self-confirming: faith in progress prompted efforts that repeatedly produced progress. The basis for the unique European belief in progress was not a triumph of secularity, but of religion. As John Macmurray put it, “That we think of progress at all shows the extent of the influence of Christianity upon us.”15

So much, then, for nonsense about the “triumph of barbarism and religion.” So too for silly claims that the “Age of Reason” dawned in about 1600. Perhaps the most utterly revealing aspect of this nonsense is the claim that it was René Descartes who led the way into, and epitomized the “Age of Reason.” In fact, Descartes very explicitly modeled himself on his Scholastic predecessors as he attempted to reason his way from the most basic of axioms (“I think, therefore I am”) to the essentials of Christian faith. Various philosophers have subsequently attacked the validity of steps in his deductive chains, but what is important is that Descartes was not revolting against an “Age of Faith,” but was entirely comfortable extending the long tradition of Christian commitment to reason.

Related Posts

Notes:

- Stark, 2003: Ch.2. ↩

- Stark, 2007: Ch.1. ↩

- Stark, 2014. ↩

- Rahner, 1975: 1687. ↩

- On Repentance 1. ↩

- Recognitions of Clement, II: LXIX. ↩

- In Lindberg and Numbers, 1986: 27-28. ↩

- Southern, 1970a: 49. ↩

- in Lindberg, 1986:27. ↩

- The City of God, XXII:24. ↩

- in Gimpel, 1961: 165. ↩

- in Gimpel, 1976: 149. ↩

- in Hartwell, 1971: 691. ↩

- Baillie, 1951; Nisbet, 1980 ↩

- Macmurray, 1938: 113. ↩

Note: Our goal is to cultivate serious and respectful dialogue. While it's OK to disagree—even encouraged!—any snarky, offensive, or off-topic comments will be deleted. Before commenting please read the Commenting Rules and Tips. If you're having trouble commenting, read the Commenting Instructions.