An Attempt to Explain Christianity to Atheists In a Manner That Might Not Freak Them Out

by Marc Barnes

Filed under Religion

Between being told that Christianity is a system of oppression, a complex way to justify burning with hatred over the existence of gay people, and a general failure of the human intellect, I begin to suspect that few people know why Christians exist at all. This is my attempt to explain why I am a Christian.

Any philosophy that claims that there exists nothing supernatural cannot grant purpose to suffering.

If some natural, secular purpose could be granted to the man suffering, then his pain would cease to be suffering and begin to be useful pain. The athlete can point to the material purpose of fitness and strength to answer the problem of his sore muscles. The old man who wakes up ever day with inexplicably sore muscles can point to no such thing. Though the pain experienced is the same — down to the last, aching twinge — the old man suffers, and the athlete does not. Suffering, to be suffering, requires the lack of a natural, secular answer.

The secular cannot answer the problem of suffering (as I’ve spoken in depth elsewhere), but suffering is still a problem we naturally want resolved. (If you don’t believe it is, develop leukemia, have a close family member die, and then try being content with not having any answers, meaning, or purpose.) We are obliged to ditch the secular and take up the religious, as a man cutting wood ditches the fork and picks up the saw. Which religion? I cannot speak for all of them, though the very existence of religion as a fundamental human institution does lend support to what I’ve just argued, that we must leave the purely secular if we want answers in this life. I can only speak for Christianity. Think of Christianity as some obscure, New Age cult — so as to judge her fairly — and I will give you her claims:

CLAIM 1: Suffering is the result of sin. If you are an atheist, freaketh not, for we know this on a purely experiential level. When we sin against others — when we steal from them, malign their names, or harm their bodies — we cause them suffering. When we sin against our nature — when we isolate ourselves, or demean our bodies — we cause our selves suffering. Suffering is the result of sin.

CLAIM 2: This verified reality is in fact the reality of the entire cosmos. The very state of human beings and the universe they inhabit is a sinful one.

Again, this is not a religious claim. The word sin is translated from the Hebrew ‘chattah’, which means ‘to miss the mark’. To say that the world is in a sinful state is to say that our world is not all it should be, that it misses the mark, that it is — in a word — imperfect. This is verifiable. We do not wish children to suffer and die, and yet we live in a world in which they do. It is entirely possible that we will have to at some point push spiky balls of calcium through our urethras. The experiences of these natural things as imperfect — to say the least — is a universal experience. We live in a world that “misses the mark” of perfection.

(OBJECTION 1: I suppose it could be argued to the contrary that the world is perfect, but we apply our human standard of perfection upon the world, and are disappointed when she doesn’t meet that standard. Both claims are statements of faith. One says, “I experience the universe as imperfect. I believe this experience corresponds to reality.” The other says, “I experience the universe as imperfect. I believe this experience does not correspond to reality.” Both are statements of belief based on a common experience — the experience of imperfection, found in kidney stones, dying children, 9/11, Katrina, etc.

The latter statement of faith — that the universe isn’t imperfect, we just believe it to be so — means human beings are far too strange to exercise rational thought. To say that what I experience as reality does not necessarily coincide with what reality actually is is to be unable to say anything at all. If what I experience as true does not necessarily coincide with what really is true, then I can hardly say “It is true that the universe is perfect.”

But this is obvious, and I digress going after the few who would argue that children dying is a matter of ultimate indifference, and that it is only our projections that make it seem otherwise.)

So the universe is imperfect. To be imperfect is to “miss the mark” of perfection. To be in a state of missing the mark is to be in a sinful state. The universe is therefore in a sinful state. As we’ve established, suffering is the natural result of sin. Thus suffering is inherent to our sinful universe.

CLAIM 3: As the universe is imperfect, God is perfect, the fullness of Perfection itself. This is first of all a simple matter of definition. If you have in your mind an imperfect God, then he is not God. But there is proof to this claim. As the philosopher Thomas Aquinas says:

“Among beings there are some more and some less good, true, noble and the like. But “more” and “less” are predicated of different things, according as they resemble in their different ways something which is the maximum, as a thing is said to be hotter according as it more nearly resembles that which is hottest; so that there is something which is truest, something best, something noblest and, consequently, something which is uttermost being.”

If God created all things, and all things are good in varying degrees, than God must be the standard of Perfection from which all things derive their relative goodness.

(Minor objection: Of course, this assumes the existence of God, which I do not aim to prove. Rather I aim to say, if there is a God, he is perfect. (I come dangerously close to bringing up St. Anselm.))

(Minor objection: Of course, this assumes the existence of God, which I do not aim to prove. Rather I aim to say, if there is a God, he is perfect. (I come dangerously close to bringing up St. Anselm.))

(OBJECTION 2: If the Christian sheeple (I’m joking) believe that God is the fullness of perfection, and that to say that our universe is sinful — or imperfect — is to say that our universe is lacking total union with God, why then, would Perfection allow our imperfection? If God is all-powerful, surely he could forever stop us from sinning, and thus from ever suffering? Is he so cruel as to allow us to suffer, children to die, etc.?

We are allowed to sin — and thus to suffer — because God loves us. If we could not refuse him, the fullness of perfection, we would be puppets attached to his celestial fingers. We could not not love God. But love, to be love, must be freely given. Perfection is meaningless if we have not the choice of imperfection. We are granted, in love, the opportunity to sin.)

CLAIM 4: Christianity answers the problem of suffering with the bizarre claim that a man who was God, the fullness of Perfection, known commonly as Jesus, “became sin”. We must listen attentively to her claim, and suspend at least a minutia of our disbelief, for we’ve already established the impossibility of an answer to the problem of suffering springing from a secular source.

(OBJECTION 3: I understand of course, that I’m not proving that God became Man. This would of course provide proving that there is a God, which is not my goal here. Rather, I beg the atheist to read this and understand that, if there is a Christ, then suffering is granted meaning, and then decide from there whether there in fact is a God, a Christ, etc.)

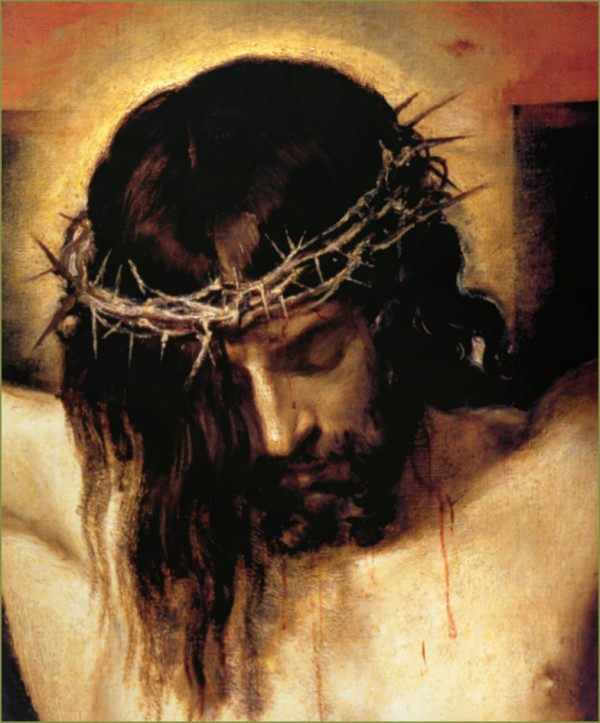

Jesus “became sin”. Sin is the act of missing the mark, of missing perfection. It follows that Jesus, in totally becoming sin, became totally absent from perfection, a claim verified by the words of Jesus on the cross: ”My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” By becoming imperfection, he is forsaken by Perfection.

We arrive at a paradox. If Jesus is God, and God is Perfection, how could Jesus “become sin” — the absence of Perfection — and thus become the absence of God? How could God become the absence of God?

He could not: He would die. If I were to become the total absence of myself, I would cease to exist. I would negate myself, as a negative number and the same positive number join to make an abyss and a zero.

CLAIM 5: God died.

All atheism has its ultimate source in Jesus Christ then, for by his death he negated the existence of God. And in his death, sin itself died, for he became sin itself. And if sin died, suffering died, for suffering is the result of sin. And if all suffering died, than death itself — the ultimate human suffering — dies.

But again, we arrive at a paradox. What happens to the man who by his death, destroys sin, and by destroying sin, destroys death? He certainly cannot die, or else he could not have destroyed death. He could not die: He would have to rise.

Claim 6:

(OBJECTION 4: Why then, if this is all true, do we still suffer, sin and die?

Time is a product of the universe, and if there is a Creator of the universe, he must exist outside of universe, and thus outside of time. The saving action of an infinite God cannot be limited to time.

It’d be a mistake to believe Christ killed death and suffering, freeing from suffering and death only those born after him. Such an expectation assumes that Christ’s sacrifice is limited to the laws of our time, that his action affects only the future, as a human action only affects the future. But his action was infinite, outside of time. He died once, for the entire world, for the past, present, and future, lifting all things to Perfection.

Thus the place without the suffering we are promised cannot be a part of earthly space and time. It must be part of the “time” of an infinite God, a time that contains all our past, present and future. Thus we are told that Christ died that we might have eternal life, life free from suffering outside of earthly time, a place Christianity has given the name Heaven.

But more than this, we suffer now for the precise reason we can sin. God will not force salvation upon us. He will not demand we claim his victory over sin and death. We are not his puppets. We must choose his salvation as we chose to sin.)

And this, finally, is the answer Christianity gives to suffering. Since Christ became all sin, and suffering is the result of sin, Christ took upon himself all suffering. Since his act was for all earthly time, this includes our current suffering. If this is true, no suffering is apart from the suffering of Christ. All is his. I am a Christian because I can acknowledge the reality that my suffering is in fact the suffering of Christ, and thereby “offer it up” with him, giving it meaning and the most glorious of purposes: The end of all suffering.

As Paul says: “Now I rejoice in what I am suffering for you, and I fill up in my flesh what is still lacking in regard to Christ’s afflictions, for the sake of his body, which is the church.” Our suffering, because it is Christ’s, saves the world.

This changes everything: To see the child with leukemia is to see Christ suffering in that child, suffering to bring the world back to Perfection. To experience agony is to cry out with the strain of lifting this fallen world to Paradise. We are called to recognize this, and to actualize this. This is why I am a Christian.

Related Posts

Note: Our goal is to cultivate serious and respectful dialogue. While it's OK to disagree—even encouraged!—any snarky, offensive, or off-topic comments will be deleted. Before commenting please read the Commenting Rules and Tips. If you're having trouble commenting, read the Commenting Instructions.