Bart Ehrman, Benedict XVI, and the Bible on the Question of Miracles

by Dr. Matthew Ramage

Filed under The Bible

“At its core, the debate about modern exegesis is not a dispute among historians: it is rather a philosophical debate.” - Joseph Ratzinger (Pope Benedict XVI)

My reflection today revolves around this poignant line from Joseph Ratzinger’s 1988 Erasmus Lecture in which he famously called for a “criticism of criticism.” In penning these words, the German cardinal was looking for a self-criticism of the modern, historical-critical method of biblical interpretation. On the part of those involved in the craft of exegesis today, this would entail the effort to identify the philosophical presuppositions we bring to our reading of the biblical text and to consider honestly the degree of certainty warranted for the conclusions we draw when it comes to things biblical.

Joseph Ratzinger: Pure Objectivity Does Not Exist

Ratzinger’s comments a generation ago remain as relevant as ever for the sort of discussions we have here at Strange Notions. Whether we are aware of it or not, both Christians and atheists bring different philosophical presuppositions to the table when we sit down to debate about the Bible. These first principles are ‘spectacles’ we wear which color our entire view of reality, including what we think is going on within Scripture. Ratzinger for his part argues that Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle applies here: “pure objectivity is an absurd abstraction,” for “the observer’s perspective is an essential determinant of the outcome of an experiment.”

What this means in terms of present purposes is that the answers to particular questions we ask of Scripture are in large part determined before we ever open up the text in the first place. What are we to make of Jesus’ miracles and of his resurrection in particular? If one is an atheist, then a natural explanation will be adduced for these phenomena. Such an explanation could take many forms: for example, a putative healing miracle could be explicable in light of modern medicine, or perhaps it was invented by the Gospel authors decades after Jesus’ life in order to convince others of his divinity.

On the other hand, a person who approaches the text assuming theism to be true will likely take the healing story at face value and attribute it to Jesus’ divine mastery over the natural order. Or perhaps the believer might take a position similar to that of the atheist but with the understanding that God in his providence shows us the face of Jesus by working through natural causes, whether that be medicine or human authors with their own agendas.

My point here is not to adjudicate which if any of these explanations best explains a given miracle story in the Gospels. Rather, I simply wish to underscore the reality that our conclusions about a given text are in large part governed by principles and commitments we had before opening up the Bible.

Throughout his career, Ratzinger has shown himself to be at once a great admirer and practitioner of modern exegesis as well as one of its most incisive critics. Far from rejecting a modern approach to Scripture, Ratzinger nevertheless admits that it “has brought forth great errors” caused in no small part by an unquestioning allegiance to certain “academic dogmas.”

A key mainstream assumption he finds particularly problematic is the belief (and I use that word here deliberately, to mean something one cannot prove) that God cannot enter in and work in human history. However improbable divine intervention in our world might appear, Ratzinger argues that this cannot be excluded a priori unless one has definitive proof that God does not exist. The miraculous is by its very nature, if you will, something unexpected and improbable. The jump from calling it improbable to impossible is what Ratzinger finds problematic, and he thinks that many people today read the Bible in this way without reflecting upon whether assuming such a conclusion is warranted or not.

Bart Ehrman: Everyone Has Presuppositions

Since this site is dedicated to fostering dialogue between believers and nonbelievers, I think it is only fair that we attempt to glimpse the same phenomena described by Ratzinger through a competing lens. One of my favorite authors in this regard is Bart Ehrman. The bestselling author, who describes himself as an agnostic, has written several books popularizing modern exegesis and challenging believers to consider more thoughtfully the origins of the Bible and Christianity. The reason I like reading Ehrman, as opposed to many other agnostic or atheist authors, lies not only in his accessible style but above all in his intellectual humility often lacking in believers and nonbelievers alike.

For this post, I simply wish to share some of his thoughts on doing historical biblical study as articulated in three of his recent books. I think there are many points of convergence with what Benedict is saying, even as the two authors ultimately come to quite different conclusions about the Christian faith.

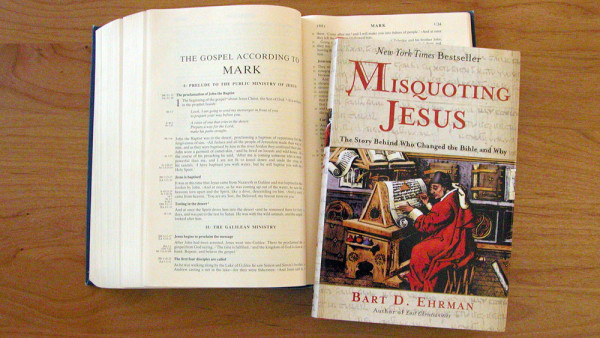

Misquoting Jesus

In this book Ehrman rightly takes issue with those who dismiss modern scholarship out of hand as if it were only practiced by the godless. I suspect that the author is right in remarking that his own books are sometimes written off by those who—whether consciously or unconsciously—perceive his arguments as threatening to their faith. In response Ehrman remarks, “These scholars are not just a group of odd, elderly, basically irrelevant academics holed up in a few libraries around the world.”

In a real sense Christians owe our modern, translated Bibles to such people—some of whom are not believers. These academics have dedicated their careers to producing Bible editions that present us, as closely as possible, with the “original” texts of Scripture.

Most people fail to realize just how complicated was the origin of the biblical texts we now take for granted as “the Bible.” For one thing, we do not possess the original letters of the New Testament fresh from their authors’ pens. Moreover, the (many and much later) copies of texts we do possess contain important variants and points of seeming contradiction among themselves.

As if that were not enough, we then still have to consider the question of how to interpret what we do have. Which manuscripts ought to be considered authoritative? Which, if any, is the one Christians are supposed to consider inspired? As Ehrman says, “If texts could speak for themselves, then everyone honestly and openly reading a text would agree on what the text says.” For better or worse, that is clearly not the case.

Jesus, Interrupted

Ehrman here again goes to great length to make clear his conviction that modern biblical exegesis is not exclusively the domain of agnostic or atheist thinkers:

"My personal view is that a historical-critical approach to the Bible does not necessarily lead to agnosticism or atheism. It can in fact lead to a more intelligent and thoughtful faith— certainly more intelligent and thoughtful than an approach to the Bible that overlooks all of the problems that historical critics have discovered over the years."

The author mentions more than once that his closest friends are both scholars and believers. According to Ehrman, “[I]t was the problem of suffering, not a historical approach to the Bible, that led me to agnosticism.” He discusses the reasons for his conviction elsewhere in his book God’s Problem.

While I do not share his convictions regarding the problem of evil as an insurmountable obstacle to belief in God, that is the topic for another thread which receives frequent attention on this site. For our purposes, let us simply recall that Ehrman’s basis for professing agnosticism has primarily to do with the problem of evil, not the problems unearthed by modern biblical scholarship.

In my estimation, Ehrman does both sides of our debate a great service in debunking the notion that we hold our respective convictions on the basis of certain proofs. For example, he writes that we can neither prove nor disprove the resurrection:

"I am decidedly not saying that Jesus was not raised from the dead. I’m not saying the tomb was not empty. I’m not saying that he did not appear to his disciples and ascend into heaven. Believers believe that all these things are true. But they do not believe them because of historical evidence. They take the Christian claims on faith, not on the basis of proof. There can be no proof."

These words may alarm some Christians who think that we can “prove” the resurrection with the internal evidence of the New Testament or any other evidence for that matter. To be sure, we Christians can and must adduce reasons for our belief and be prepared to defend our faith against objections. But Ehrman is perfectly right to push us on the reality that these reasons do not amount to a definitive proof. That, indeed, is why we call it faith, not science.

Again, the Catholic position is by no means saying that faith is “unscientific” or at odds with science. Rather, the point here is that the Christian and the atheist may look at the same evidence and draw different conclusions because of our prior commitments which involve a decision to view the Bible through the lens of faith or not.

How Jesus Became God

Ehrman probes the issue of belief in the resurrection at greater length in his most recent work. Here he rightly criticizes an all-too common response of Christians when they are faced with the findings of modern biblical scholarship:

"The reason historians cannot prove or disprove whether God has performed a miracle in the past—such as raising Jesus from the dead—is not that historians are required to be secular humanists with an anti-supernaturalist bias. I want to stress this point because conservative Christian apologists, in order to score debating points, often claim that this is the case. In their view, if historians did not have anti-supernaturalist biases or assumptions, they would be able to affirm the historical 'evidence' that Jesus was raised from the dead."

Unfortunately, I have seen plenty in my years of teaching a mostly-Catholic audience to confirm Ehrman’s observations. Sometimes Catholic writers and speakers write off modern scholarship tout court with the use of scare quotes, calling modern thinkers “scholars” as if they were not actually scholars because they lack or at least seem to lack the faith that the Christian thinks is required for them to have any competence at all in their field.

Regarding evangelical Christians—Ehrman’s former self which I take to be his principal audience—the author adds a fascinating point to his criticism above:

"I should point out that these Christian apologists almost never consider the 'evidence' for other miracles from the past that have comparable— or even better—evidence to support them: for example, dozens of Roman senators claimed that King Romulus was snatched up into heaven from their midst; and many thousands of committed Roman Catholics can attest that the Blessed Virgin Mary has appeared to them, alive—a claim that fundamentalist and conservative evangelical Christians roundly discount, even though the 'evidence' for it is very extensive…Protestant apologists interested in 'proving' that Jesus was raised from the dead rarely show any interest in applying their finely honed historical talents to the exalted Blessed Virgin Mary."

This point of criticism is difficult for any Christian to address, and a robust response is needed. While it is not my point here to take on this problem, I would simply note that for the Catholic tradition God’s grace (including the possibility of miracles) is not constrained within the visible confines of the Catholic Church. Unlike some Christians, Catholics are not intrinsically opposed to the possibility of a non-Christian performing or experiencing a miracle.

In a later section of this book, Ehrman turns aside from the above considerations to consider in more detail the fundamentals of how to do history properly. At a pivotal point he says something which I could have mistaken as coming from the pen of Pope Benedict had I not known otherwise:

"The first thing to stress is that everyone has presuppositions, and it is impossible to live life, think deep thoughts , have religious experiences, or engage in historical inquiry without having presuppositions. The life of the mind cannot proceed without presuppositions. The question, though, is always this: What are the appropriate presuppositions for the task at hand?"

This is one of the questions that interests me most and which I think lies at the heart of Pope Benedict’s statement that the debate in exegesis is at bottom a philosophical one. We can never completely suspend our biases, but we can at least do our best to remain conscious of their presence and engage in a self-critique that helps to purify our thought and attune it with the breadth of knowledge we can gain from the sources available to us.

In this critique, a few pivotal questions emerge: Whose philosophical presuppositions best position us for an accurate understanding of the nature of things? Which ones best enable us to live well? And what would the process for making such a determination look like? These are issues I hope to take up in my next post at Strange Notions, but here my concern remains much more basic in showing that there is a problem recognized by good thinkers on both sides of the religious/non-religious aisle.

I would like to draw these remarks to a close with a word on complete objectivity which Ehrman, like Benedict, rejects as a possibility in our effort to interpret the Scriptures. As Ehrman states, “This is one of the great ironies of modern religion: more than almost any other religious group on the planet, conservative evangelicals, and most especially fundamentalist Christians, are children of the Enlightenment.”

Both modern Christians and modern skeptics yearn for a level of certitude that simply does not exist or exists for only a very limited range of truth claims. In Ehrman’s words, “[F]aith in a miracle is a matter of faith, not of objectively established knowledge.” For instance, if Jesus really did perform the miracles the gospels claim he did, then this would help explain how Jesus’ opponents could deny these actions in the face of evidence that God was working through him.

It is the same dynamic that we find in Jesus’ parable of the Rich Man and Lazarus. The rich man suffering in Hades begs Father Abraham to send someone to his living relatives and warn them about the place of torment, to which Abraham replies, “If they do not hear Moses and the prophets, neither will they be convinced if someone should rise from the dead” (Luke 16:31). Here again, people could look at the same evidence and draw different conclusions, a process largely determined by their prior convictions.

So did Jesus really come back from the dead as the above parable intimates? And was this parable even uttered by the historical Jesus in the first place? These are important questions which—for both believers and nonbelievers alike—are often answered even before they are asked. In the following post we will continue the conversation in more detail, but for now this is a good place to begin our discussion.

Related Posts

Note: Our goal is to cultivate serious and respectful dialogue. While it's OK to disagree—even encouraged!—any snarky, offensive, or off-topic comments will be deleted. Before commenting please read the Commenting Rules and Tips. If you're having trouble commenting, read the Commenting Instructions.