Why God Provides Room to Build a Better World

by Fr. Robert Spitzer

Filed under The Problem of Evil

NOTE: This is the last in our four-part series by philosopher Fr. Robert Spitzer addressing the question, "Why Would God Allow Suffering Caused by Nature?" Instead of focusing on the existence of moral evil, or suffering caused by the free choice of humans, he examines why an apparently good God would create an imperfect world replete with natural disasters, physical disabilities, and unavoidable heartache. Find the other parts of the series here.

We now move from an individual and personal perspective on suffering to a social and cultural perspective. We saw in the previous three sub-sections how God uses an imperfect world (and the challenge/suffering it can cause) to call and lead individuals toward life-transformations, courage, self-discipline, empathy, humility, love’s vulnerability, and compassion. However, the value of an imperfect world and suffering is not limited to this. God can also use suffering to advance the collective human spirit, particularly in culture and society. There are three evident manifestations of this collective-cultural-societal benefit of an imperfect world and suffering: (1) interdependence, (2) room to make a better world, and (3) the development of progressively better social and cultural ideals and systems. Each will be discussed in turn.

Interdependence

We cannot be completely autonomous – we need each other not only to advance but also to survive. Our imperfect world has literally compelled us to seek help from one another, to open ourselves to others’ strengths, to make up for one another’s weaknesses, and to organize ourselves to form a whole which is greater than the sum of its parts. We could say that our imperfect world is the condition necessary for the possibility of interdependence, and that interdependence provides an almost indispensable impetus to organize societies for mutual benefit.

The reader might respond that this is a somewhat cynical view of human nature because we probably would have formed societies simply to express empathy and love. I do not doubt this for a moment. However, I also believe that necessity is not only the mother of invention, but also the mother of social organizations for mutual benefit and specialization of labor. An imperfect world complements the human desire for empathy and love. While empathy and love allow us to enjoy one another, the imperfect world challenges us to extend that love to meeting others’ needs and making up for others’ weaknesses. Challenges (arising out of an imperfect world) induce us to extend our empathy, friendship, and enjoyment of one another into the domain of meeting one another’s needs, organizing ourselves for optimal mutual benefit, and creating societies which take on a life of their own beyond any specific individual or group of individuals. Yet an imperfect world does far more than this. It calls us to make a better world, to the discovery of the deepest meaning of justice and love, and even to create better cultures and systems of world organization.

Room to Make a Better World

An imperfect world reveals that God did not do everything for us. He has left room for us to overcome the seeming imperfections of nature through our creativity, ideals, and loves – not merely individual creativity, ideals, and loves, but also through collective creativity, ideals, and loves. As noted above, individuals can receive a tremendous sense of purpose and fulfillment by meeting challenges and overcoming adversity. Yet we can experience an even greater purpose and fulfillment by collectively meeting challenges which are far too great for any individual; challenges which allow us to be a small part of a much larger purpose and destiny within human history.

It would have been noble indeed, and a fulfillment of both individual and collective purpose to have played a small part in the history of irrigation, the synthesis of metals, the building of roads, the discovery of herbs and medicines, the development of elementary technologies, the development of initial legal codes, the initial formulation of the great ideas (such as justice and love), the discoveries of modern chemistry, modern biology, modern medicine, modern particle physics, contemporary astronomy and astrophysics, the development of justice theory, inalienable rights theory, political rights theory, economic rights theory, contemporary structures of governments, the development of psychology, sociology, literature, history, indeed, all the humanities, arts, and social sciences; to have played a small part in the great engineering and technological feats which have enabled us to meet our resource needs amidst growing population, to be part of the communication and transportation revolutions that have brought our world so much closer together; to have been a small part of the commerce which not only ennobled human work, but also generated the resources necessary to build a better world; to have been a small part in these monumental creative efforts meeting tremendous collective challenges and needs in the course of human history.

Yet, none of these achievements (and the individual and collective purpose and fulfillment coming from them) would have been possible without an imperfect world. If God had done everything for us, life would have been much less interesting (to say the least) and would have been devoid of the great purpose and achievement of the collective human spirit. Thank God for an imperfect world and the challenges and suffering arising out of it. We were not created to be self-sufficient, overly-protected “babies,” but rather to rise to the challenge of collective nobility and love – to build a better world.

The Development of Progressively Better Social Ideals

We not only have the capacity to meet tremendous challenges collectively, we can also build culture – the animating ethos arising out of our collective heart which impels us not only toward a deeper and broader vision of individuals, but also of groups, communities, societies, and the world. This broader and deeper vision includes a deeper appreciation of individual and collective potential and therefore a deeper respect for the individual and collective human spirit. Thus, we have the capacity not only to build a legal system, but also to infuse it with an ideal of justice and rights, a scrupulous concern for accuracy and evidence, and a presumption of innocence and care for the individual. We have the ability not only to make tremendous scientific discoveries, but also to use them for the common good rather than the good of just a privileged class. We have the ability not only to build great structures, but also to use our architecture to reflect the beauty and goodness of the human spirit. We have the capacity not only to do great research but also to impart the knowledge and wisdom gained by it in a humane and altruistic educational system. And the list goes on.

Perhaps more importantly, we have the capacity to build these more beneficent cultural ideals and systems out of the lessons of our collective tragedy and suffering. One of the greatest ironies of human history, it seems to me, is the virtual inevitability of the greatest human cultural achievements arising out of the greatest moments of human suffering and tragedy (whether these be caused by natural calamities like the plague or more frequently out of humanly induced tragedies such as slavery, persecution of groups, world wars, and genocide):

- Roman coliseums (butchering millions for mere entertainment) seem eventually to produce Constantinian conversions (taking an entire empire toward an appreciation of Christian love)

- Manifestations of slavery seem to lead eventually to an abolitionist movement and an Emancipation Proclamation

- Outbreaks of plague seem to lead eventually to advances in medicine and public health, as well as a deeper appreciation of individual life and personhood

- Manifestations of human cruelty and injustice seem to lead eventually to inalienable rights and political rights theories (and to systems of human rights)

- Large-scale economic marginalization and injustice seem to lead eventually to economic rights theories (and to systems of economic rights)

- World wars seem to lead eventually to institutions of world justice and peace

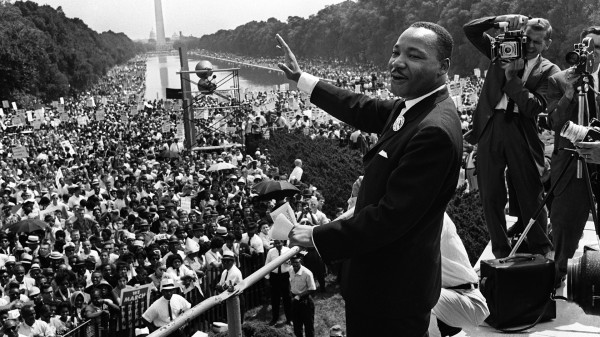

There seems to be something in collective tragedy and suffering that awakens the human spirit, awakens a prophet or a visionary (such as Jesus Christ, St. Francis of Assisi, William Wilberforce, Mahatma Gandhi, or Martin Luther King, Jr.), which then awakens a collective movement of the human heart (such as the abolitionist movement), which then has to endure suffering and hardship in order to persist, but when it does persist, brings us to a greater awareness of what is humane.

Out of the ashes of collective tragedy seems almost inevitably to arise a collective advancement in the common good and human culture; and more than this – a collective resolve, a determination of the collective human spirit which proclaims, “never again;” and still more – a political-legal system to shepherd this collective resolve into the future.

As may now be evident, the greatest collective human achievements in science, law, government, philosophy, politics and human ideals (to mention but a few areas) seem to have at their base not just an imperfect world, not just individual suffering, not just collective suffering, but epic and even monumental collective suffering.

Was an imperfect world necessary for these greatest human achievements? It would seem so (at least partially); otherwise there would have been no room to grow, no challenges to overcome (either individually or collectively), and no ideals to be formulated by meeting these challenges. God would have done them all for us.

Nothing could be worse for a child’s development and capacity for socialization than an overprotective parents who think they are doing the child a favor by doing her homework for her, constructing her project for her, thinking for her. To remove all imperfections from a child’s living conditions; to take away all challenges and opportunities to meet adversity, all opportunities to rise above imperfect conditions; to take away all opportunities to create and invent a better future; and to remove the opportunity to exemplify courage and love in the midst of this creativity would be tantamount to a decapitation. God would no more decapitate the collective human spirit than a parent would a child; and so, God not only allowed an imperfect world filled with challenge and adversity, He created it.

We must remember at this juncture that God’s perspective is eternal. From the Catholic perspective, God intends to redeem every scintilla of our suffering and to transform it into the symphony of eternal love which is His kingdom. Therefore, a person who suffered in a Nazi concentration camp (which eventually led to the U.N. Charter of Human Rights and to the current system of international courts) did not suffer for the progress of this world alone, as if he were merely a pawn in the progress of the world. Rather, his suffering is destined for eternal redemption by an unconditionally loving and providential God who will bring courage, self-discipline, empathy, humility, love’s vulnerability, compassion, and agape to its fullest unique expression for all eternity. At the moment of what seems to be senseless suffering and death, God takes the individual into the fullness of His love, light, and life while initiating a momentum toward a greater common good within the course of human history. That means we must continually take precautions against reducing ourselves to mere immanentists, for the God of love redeems each person’s suffering individually and eternally while using it to induce and engender progress toward His own ideal for world culture and the human community.

The above points only answer part of our question about the necessity of suffering to advance the common good; for even if an imperfect world were truly necessary for such advancement, it does not seem that something as monstrous as a world war would be so necessary. Perhaps. But here is where moral evil and human freedom exacerbate the conditions of an imperfect world. Unlike natural laws, which blindly follow the pre-patterned sequences of cause and effect, human evil has embedded in it injustice, egocentrism, hatred, and cruelty which are all truly unnecessary. Nevertheless, even in the midst of the unnecessary and gratuitous suffering arising out of moral evil, the human spirit (galvanized by the Holy Spirit, according to my faith) rises above this suffering and seems eventually to produce advancements in culture and the common good in proportion to the degree of suffering.

In conclusion, the annals of human history are replete with examples of how tremendous moments of collective human suffering (whether caused by human depravity or the imperfections and indifference of nature, or both) induced, engendered, accelerated, and in many other ways helped to create the greatest human ideals and cultural achievements. If one has faith one will likely attribute this “phoenix out of the ashes” phenomenon to the Holy Spirit working within the collective human spirit. If one does not have faith, one will simply have to marvel at the incredible goodness of the collective human spirit. (And ask, was it possible for us to do this by ourselves?)

In any case, the imperfect world and the history of human suffering have given rise to a concrete reality of remarkable beauty and goodness in the areas of justice, rights, legal systems, governance systems, medicine, biology, chemistry, physics, psychology, sociology, and every other discipline which has as its noble end the advancement of the common good.

Without an imperfect world, without some suffering in the world, I find it very difficult to believe that any of this would have arisen out of the collective human spirit in the course of history.

It would seem that the price paid in pain has been at least partially offset by the gains made in culture, society, the individual spirit, and the collective human spirit. I do not mean to trivialize the history of human suffering and tragedy nor the lives of individuals ruined by human injustice and an imperfect natural order. Yet we should not fail to find some hope in light emerging from darkness, and goodness emerging from evil. Inasmuch as God is all-powerful and all-loving, He can seize upon this goodness and light to reinforce its historical momentum, and more importantly to transform it into an unconditionally loving eternity. An imperfect world shaped by an imperfect, yet transcendently good human spirit brought to fulfillment by an unconditionally loving God, may well equate to an eternal symphony of love.

Related Posts

Note: Our goal is to cultivate serious and respectful dialogue. While it's OK to disagree—even encouraged!—any snarky, offensive, or off-topic comments will be deleted. Before commenting please read the Commenting Rules and Tips. If you're having trouble commenting, read the Commenting Instructions.