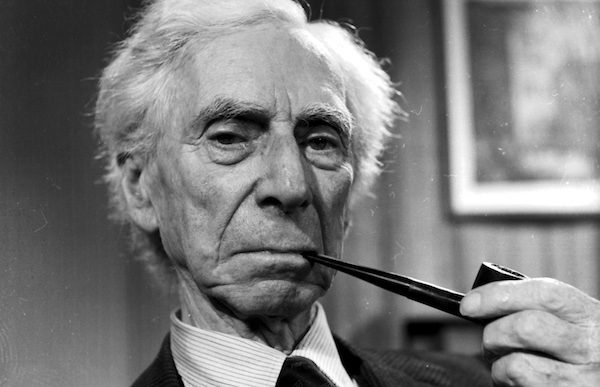

Was Bertrand Russell Right About Thomas Aquinas?

by Joe Tulloch

Filed under Philosophy

Bertrand Russell was one of the most prominent philosophers of the 20th century, and an outspoken skeptic. His bestselling book A History of Western Philosophy (which was cited as one of the reasons for his 1950 Nobel Prize in Literature) contains a short chapter in which he examines St Thomas Aquinas’ life and work, concluding with the following, damning remark:

There is little of the true philosophic spirit in Aquinas. He does not, like the Platonic Socrates, set out to follow wherever the argument may lead. He is not engaged in an inquiry, the result of which it is impossible to know in advance. Before he begins to philosophize, he already knows the truth; it is declared in the Catholic faith. If he can find apparently rational arguments for some parts of the faith, so much the better; if he cannot, he need only fall back on revelation. The finding of arguments for a conclusion given in advance is not philosophy, but special pleading. I cannot, therefore, feel that he deserves to be put on a level with the best philosophers either of Greece or of modern times.1

This, like a lot of Russell’s criticisms of philosophers he disagrees with, is unfair, inadequate, and misleading, resting on very basic misconceptions, and I want, in this blog post, to briefly argue so.

First, however, it ought to be said that Russell does not only have negative things to say about Aquinas – on the contrary, he makes a point of listing a good number of positive elements of his philosophy. He praises Aquinas’ deft synthesis of Aristotelianism and Christianity, as well as its originality, noting that in his day he was considered a “bold innovator”, whose doctrines were condemned by the universities of Oxford and Paris. He also commends his practise of stating opposing arguments before developing his own, although his remark that this is done “often with great force, and almost always with an attempt at fairness” renders this an imperfect compliment. Aquinas does well in clearly distinguishing doctrines derived from reason and doctrines derived from faith, he notes, and “knows Aristotle well, and understands him thoroughly, which cannot be said of any earlier Catholic philosopher”.2

What are we to make of Russell’s assessment? Perhaps even those sympathetic to Aquinas might feel that there is some force to it – isn’t there something pretty questionable about deciding what you believe first, and then searching for arguments to back it up later?

The first problem with the assessment is the very basic one that it is unsupported by evidence – Russell fails to provide a single example of Aquinas’ failure to “follow the argument where it leads”. He ignores, moreover, the frequent examples of Aquinas doing what appears to be the exact opposite; namely, accepting unpalatable conclusions when the facts seem (to him) to suggest that he ought to. Many philosophers before him had held that it can be demonstrated, by pure reason, that the universe is not eternal (this is still a position held by a good number of thinkers), and whilst it would no doubt be very convenient from a religious point of view if this were true – as it might point to a creator – Aquinas, after considering the subject in some detail, comes to the conclusion that it is not.

So what about the broader claim that Aquinas’ whole method is unphilosophical, since he starts from the position that the Catholic faith is true, and then looks for arguments to that effect? As the Oxford philosopher Sir Anthony Kenny remarks,3 this is a comment that comes pretty strangely from Russell, who spent a few hundred pages of his book Principia Mathematica trying to prove (starting from a few logical axioms) that 1 + 1 = 2, something which, we can assume, he already believed before he began. More fundamentally, I think that Russell's assumption that Aquinas' religious belief is independent of reason is wrong, or, at best, unevidenced. Of course, being raised Catholic, Aquinas will have been religious before he was able to give any reason to be, but this doesn't imply that his later, mature faith was not rational. As he grew older, and became capable of reasoning about religion, and the world in general, it seemed (to him) that evidence confirmed his beliefs, but if it had not, it seems very unlikely that he would have remained Christian. Aquinas is famous for his insistence on the importance of reason, even in the face of certain church authorities, who claimed that it ought to be subservient to faith; his reasoning was that if the Christian religion is true, and reason leads to truth, then it makes no sense for the two to be in conflict. If he had found them to be in conflict – if, for instance, he was not convinced by his own Five Ways (arguments for the existence of God), and found prayer useless, or the problem of evil irresolvable, or the Bible seriously unreliable, and so on, then there is good reason to think that he would have abandoned religion.

If this is true, then his religious belief is really, contrary to Russell, no different, and no more intellectually suspicious, than the vast majority of the beliefs held by everyone – learnt, pre-rationally, in childhood, and later confirmed or rejected on the basis of mature reflection and experience. Think about the way you learnt that London is the capital of England, or that democracy is a fairer political system than fascism - these are beliefs which you learnt uncritically as a child, and later grew to understand and accept (or deny) as you grew older – just, I would suggest, as Aquinas did with religion. This does not, of course, show that his belief is justified – I've said nothing about whether the reasons for his belief are any good. It does, however, suggest that if Aquinas is to be criticised, it must be because of the quality of the evidence he uses, and not on the basis that his religious faith is independent of it.

A final problem with Russell's analysis lies in his assessment of Aquinas’ view of the interaction between faith and reason, when he writes that “If he can find apparently rational arguments for some parts of the faith, so much the better; if he cannot, he need only fall back on revelation”. This accusation neglects a very simple and fundamental distinction in Aquinas’ thought, that between doctrines which can be known by reason and arguments which, by their very nature, cannot be. According to Aquinas, the existence of a prime mover, an uncaused cause of the universe, would be a fact of the first kind – he thinks that anyone, no matter where and when they are born, will come to belief in this sort of supernatural power if they think hard and well enough. The Trinity, he thinks, is a fact of the second kind – no amount of unaided reason could ever bring anyone to the conclusion that the uncaused cause has one nature in three persons; this can only be known through God's revelation.

In providing arguments for some doctrines and not for others, then, Aquinas is not, as Russell suggests, just scrambling around for arguments where he’s able to, and making excuses where he isn’t, but relying on what is a very sensible distinction between two types of fact. For analytical philosophers such as Russell, such distinctions are bread and butter, and it reflects very poorly on him to have so obviously missed the point.

It can, then, be seen that Russell's criticisms of Aquinas hold little water. Such misjudged attacks are, unfortunately, characteristic of him – his treatment of a number of important thinkers and schools of thought in the History of Western Philosophy has come under criticism, as has his condemnation of his one-time protégé Ludwig Wittgenstein, of whom he became extremely dismissive after they fell out (and who then went on to become probably the most significant philosopher of the 20th century). Perhaps we would do well to emulate Aquinas, who, as we saw, always made sure to treat his opponents charitably, rather than Russell, when we have criticisms to deliver.

Related Posts

Notes:

Note: Our goal is to cultivate serious and respectful dialogue. While it's OK to disagree—even encouraged!—any snarky, offensive, or off-topic comments will be deleted. Before commenting please read the Commenting Rules and Tips. If you're having trouble commenting, read the Commenting Instructions.