Chesterton, Shaw, and the Effect of Laughter on Insult

by Marc Barnes

Filed under Anthropology

The Internet hath done wondrous deeds, but raising the intellectual bar cannot counted among them. This became clear when I realized the question man alone has the dignity to ask—Am I a creature or an accident?—is being answered by taking screenshots of our oppositions’ Facebook statuses, rebutting them in Impact font, and posting them in a forum appropriated for the caress of our preconceived notions and the heavy petting of our unexamined faith. In this climate of awful, between the “God Hates Gays” meme and the “Atheism Causes War” rebuttal, I sympathize with the man who dismisses current atheistic/theistic dialogue as a joke.

But the problem with all this is that it’s not a joke. If there were jokes, there would be understanding, and an untwisting of sneers besides. The power of humor is not that it makes the serious frivolous, but that it unites opposites, and binds contraries in communion. By opening the lungs to laugh, humor opens the heart to hear, rendering a man absurdly vulnerable to anything his opposition wishes to say.

Take, for instance, the fact that it is acceptable to insult a man’s mother to his face if—and only if—you can make him laugh while doing it. ‘Yo Momma’ jokes bear testimony to this bizarre truth, that there are moments when we will enjoy precisely that which has been deemed utterly distasteful. In fact, it is entirely acceptable to call a man any manner of names, to insult his upbringing, his occupation, the faithfulness of his wife, his education, his love life—if and only if he laughs. Laughter negates insult.

By what witchcraft? I’m not sure. But its seems that all jokes are inside jokes in that they bring two men into the same sphere to dwell in communion with each other. It’s impossible not to like the man who makes you laugh, for in that moment of laughter you share with him the joke. You are his brother.

Now if a joke allows a man to bear an insult to his person, and bear it willingly, then surely a joke would allow a man to bear an insult to his worldview and his philosophy, and bear it willingly? Debate is, when all is said and done, the constructive insult of another man’s philosophy. This does not necessitate that it be bitter. In fact, it demands that it be good-natured. It demands that the insulting, divisive nature of debate be elevated by the communicative, brotherly nature of humor, if one desires to convince his opponent.

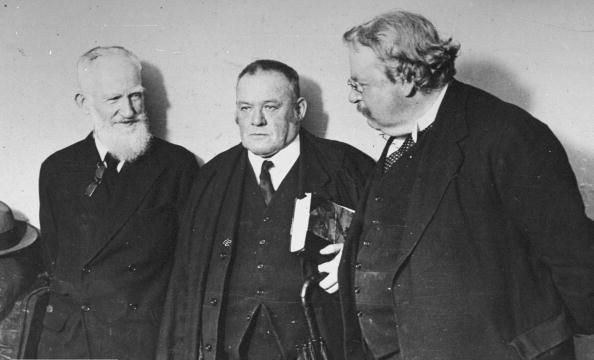

I look to the debates of G.K. Chesterton and Bernard Shaw as my example, the former a Catholic and a distributist, the latter an atheist and a socialist. Their ability to joke—and to stay friends—in the midst of such heated debate is no accident. It is precisely because they could joke that the debates were so heated—there was a real danger of someone being converted. Shaw, in defending his desire to abolish private property, said:

"If I own a large part of Scotland I can turn the people off the land practically into the sea, or across the sea. I can take women in child-bearing and throw them into the snow and leave them there. That has been done. I can do it for no better reason than I think it is better to shoot deer on the land than allow people to live on it. They might frighten the deer.

But now compare that with the ownership of my umbrella. As a matter of fact the umbrella I have to-night belongs to my wife; but I think she will permit me to call it mine for the purpose of the debate. Now I have a very limited legal right to the use of that umbrella. I cannot do as I like with it. For instance, certain passages in Mr. Chesterton’s speech tempted me to get up and smite him over the head with my umbrella. I may presently feel inclined to smite Mr. Belloc. But should I abuse my right to do what I like with my property—with my umbrella—in this way I should soon be made aware—possibly by Mr. Belloc’s fist—that I cannot treat my umbrella as my own property in the way in which a landlord can treat his land. I want to destroy ownership in order that possession and enjoyment may be raised to the highest point in every section of the community. That, I think, is perfectly simple..."

To which G.K. Chesterton responds:

"Among the bewildering welter of fallacies which Mr. Shaw has just given us, I prefer to deal first with the simplest. When Mr. Shaw refrains from hitting me over the head with his umbrella, the real reason—apart from his real kindness of heart, which makes him tolerant of the humblest of the creatures of God—is not because he does not own his umbrella, but because he does not own my head. As I am still in possession of that imperfect organ, I will proceed to use it to the confutation of some of his other fallacies...

I fully agree with Mr. Shaw, and speak as strongly as he would speak, of the abomination and detestable foulness and sin of landlords who drove poor people from their land in Scotland and elsewhere. It is quite true that men in possession of land have committed these crimes; but I do not see why wicked officials under a socialistic state could not commit these crimes. That has nothing to do with the principle of ownership in land. In fact these very Highland crofters, these very people thus abominably outraged and oppressed, if you asked them what they want would probably say, 'I want to own my own croft; I want to own my own land.'"

Perhaps I’m the only one who enjoyed all that umbrella talk, but I hope I am not the only who recognizes that the exchange of these two men is miles beyond—in quality, clarity, and convictions—the binary, right/left, atheist/theist debates we witness today.

The current God Debate does not seek to make its opponent laugh, but to make an already sympathizing audience sneer. One wonders whether debates aim to convince at all—an object which demands the respect and love of the other—or whether they exist entirely to publicly dismiss others, a thrill unique to those—myself included—who forsake the pursuit of truth for that of popularity. Sarcasm, wit and humor—which all have their place—are wasted. Humor is one of the most powerful weapons human communication can wield, for it makes a friend out of an enemy, but we are too intent using it for the sake of our already-nodding audience to bother using it for the sake of conveying the truth.

Chesterton said “It is the test of a good religion whether you can joke about it,” and this seems to me true, for to joke about your philosophy is to invite others into it—everyone can laugh at a joke. Let us not be so smug as to disdain joining in.

Related Posts

Note: Our goal is to cultivate serious and respectful dialogue. While it's OK to disagree—even encouraged!—any snarky, offensive, or off-topic comments will be deleted. Before commenting please read the Commenting Rules and Tips. If you're having trouble commenting, read the Commenting Instructions.