Is there Life Elsewhere in the Cosmos?

by Magis Center of Reason and Faith

Filed under Cosmology

The December Wall Street Journal editorial by Eric Metaxas, "Science Increasingly Makes the Case for God", has generated significant interest and discussion. Metaxas’ main point is that the probability of life existing in our inhospitable universe is so close to zero that only a supernatural explanation (i.e., God) can account for our existence here on Earth.

We agree with Mr. Metaxas that the odds against an anthropic universe are staggeringly high, but we’re not as convinced that extraterrestrial life is as improbable as his article implies. Metaxas theorizes that the high number of factors necessary to support life here on earth makes it virtually impossible that life exists elsewhere. But because we now have the ability to detect and even categorize remote planets, the research has gone beyond the purely theoretical to now include observational data. It is our purpose here to summarize this new data.

Science is just beginning to probe the skies for exoplanets. The first confirmed planet orbiting a star similar to our sun was discovered in 1996 by the Swiss team of Michel Mayor and Didier Queloz. Discoveries accelerated a decade later with the launch of the 2006 French CoRoT and the 2009 NASA Kepler space missions, and currently there are over 1800 confirmed exoplanets with thousands more under investigation.

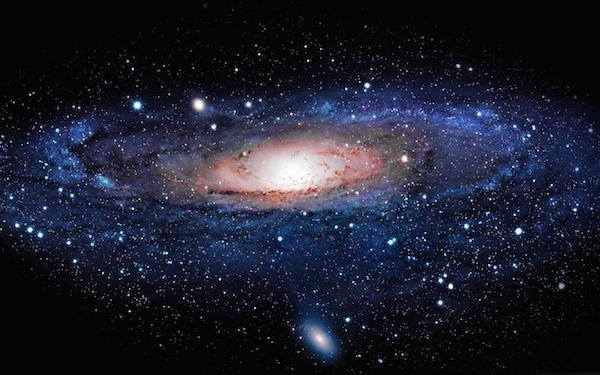

Bearing in mind that all of these planets are located in our galaxy—the Milky Way, which houses 100-200 billion stars, and is but one of an estimated 100-200 billion galaxies, one quickly realize that there are a lot of places to look. Current technology however, limits our search to neighboring regions of the Milky Way. Still, as evidenced by the numbers above, our stellar neighborhood has proven to be a fruitful starting point.

The next question is whether or not any of these planets are habitable by life forms similar to those found on earth? To be clear, our use of the term “life” refers to any living organism more complex than microbes (e.g., bacteria) This is not a slight on bacteria, which are amazingly interesting and adaptable organisms, but rather a recognition that bacteria on earth live in temperatures that would fry or freeze other forms of life and thrive in pressure and radiation that would kill anything else in minutes. In other words, because bacteria could theoretically exist almost anywhere, we need to find planets with conditions capable of supporting more fragile species for the research to be meaningful.

To this end, hundreds of scientists around the world are working on the problem of identifying habitable planets. The largest effort by far is NASA’s in-house research of the data collected by its Kepler Spacecraft. To provide a perspective of the scope of this effort, a search of the NASA ADS (academic papers library) for papers with the keyword ‘habitability’ will return a list of some 18000 papers! Furthermore, because most of the data collected by Kepler is publicly available other researchers can analyze it and draw their own conclusions.

One such researcher is Louis Irwin, Ph.D., a biologist at the University of Texas at El Paso. Dr. Irwin’s team has formulated a “biological complexity index” (BCI), which rates planets on a scale of 0 to 1.0 according to the number and degree of characteristics assumed to be important for supporting multicellular life. Dr. Irwin’s team surveyed 637 exoplanets and found that 11 had a BCI rating higher than Jupiter’s moon Europa, which has both oxygen and water, and possibly even a subsurface global ocean. Based on these findings, the Irwin group estimated that there could be 100 million habitable planets in the galaxy.

Dr. Irwin’s figure of 11 habitable planets correlates with NASA’s finding that 10 out of the 603 planets they studied are in the ‘habitable zone”, but because of a different way of calculating the number of planets per stars in our galaxy, the Kepler scientists estimated that up to whopping 4 billion exoplanets in the Milky Way could support life.

Curiosity has us look up at a starlit sky and wonder if we’re alone. Could life exist out there? Most astronomers will say yes to this because science believes that the universe is fairly homogeneous - such that Earth does not inhabit a special place in space. If life could develop in our corner of the Universe, which has no unique physical properties, then perhaps it could develop in another corner of the Universe.

Still, the universe is a really big place and the distance between us and other stars (even in our own galaxy) is so large that finding indications of planet habitability by careful analysis of light (the present technique) is child’s play in comparison to actually sending a spaceship to another solar system to verify our suspicions. To illustrate, in May of 1980 the Voyager 1 rocket concluded its exploration of Jupiter and Saturn and started its journey towards interstellar space. Twenty -two years later in August 2012 it crossed the Heliopause, the theoretical boundary of the solar system. At Voyager’s current speed of 38,000 mph it would take 80,000 years for the ship to reach our nearest stellar neighbor, Proxima Centauri, which is a “mere” 4.2 light years away.

The discovery and classification of exoplanets based on habitability is an exciting new field that is worthy of our interest and attention, and it’s far too early in the investigation to conclude whether or not we are alone in the galaxy, much less the universe. But it’s also important to keep in mind that even if our research indicates that there are potentially billions of habitable planets out there, the vast distances between the stars may mean that, without a dramatic increase in our technological capabilities, we’ll really never know if any of these exoplanets support life.

This article was co-written by Joseph G. Miller, the Executive Director of the Magis Center of Reason and Faith, and Marisa Cristina March, Ph.D., Postdoctoral Researcher at the University of Penn.

Related Posts

Note: Our goal is to cultivate serious and respectful dialogue. While it's OK to disagree—even encouraged!—any snarky, offensive, or off-topic comments will be deleted. Before commenting please read the Commenting Rules and Tips. If you're having trouble commenting, read the Commenting Instructions.