The Existential Classic Behind Woody Allen’s “Irrational Man”

by Matthew Becklo

Filed under Movies/TV

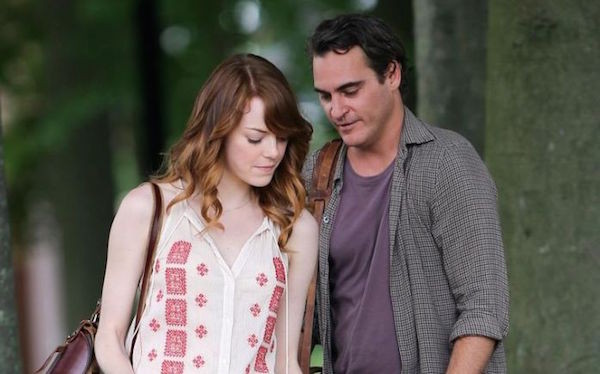

Irrational Man, the 45th film from the prolific Woody Allen, starts Joaquin Phoenix as Abe Lucas, a philosophy professor in a small town undergoing an “existential crisis.” You suffer from despair,” Emma Stone (who plays one of his students) tells him – and it appears she’s right. The professor has a drinking problem, suffers from “dizziness and anxiety,” and is tormented by a quest to commit a “meaningful act.”

Early reviews suggest that Irrational Man will go the way of Crimes and Misdemeanors and Match Point: Lucas’ meaningful act will be the perfect murder. The trailer’s lighthearted tone notwithstanding, a crazed Phoenix wandering through a park portends the kind of downward spiral we saw in Blue Jasmine.

All of this is familiar territory for Woody Allen fans – not only because of the murder plot, but also because of the emphasis on “the question of the meaning of being” that runs throughout his films. There was the neurotic character Mickey (Hannah and Her Sisters) who becomes convinced that he has a brain tumor, only to find out that he has something much worse: meaninglessness. Then there was that scene (one of my personal favorites) in Play It Again Sam, which – with sophisticated New Yorkers, an art museum, romantic attraction, and talk of suicide punctuated with a joke – is as good a minute-long summation of Allen’s movies as you could ever hope to find. In a word, Woody Allen has always been an existentialist.

In fact, Irrational Man takes its title verbatim from a 1958 book by existential philosopher William Barrett. As the Guardian notes, Barrett’s book – which was responsible for introducing existentialism to the English speaking world – “no doubt formed part of Allen’s self-taught intellectual life in the late 50s and early 60s.”

Barrett (following Matthew Arnold) argues that the West is divided into two competing impulses: Hebraism and Hellenism. The first, which we receive from the Jewish religious tradition, is a philosophy of action, moral law, and ontological finitude – in a word, the vital. The second, which we receive from the Greek philosophical tradition, is a philosophy of knowledge, theoretical science, and epistemological certitude – in a word, the rational. The first is earthy: it looks “down” on the concrete and particular, focusing on individual people and what they stake their lives on. The second is ethereal: it looks “up” to the abstract and timeless, focusing on universal ideas and what they demonstrate. The first gives us saints, mystics, and artists; the second gives us philosophers, scientists, and industrialists.

Barrett links the second impulse, Hellenism, with the modern philosophical tradition inaugurated by Descartes in the seventeenth century. With its removal of the spirit from nature, its method of detached observation, and its quest for mathematical certainty and industrial conquest, Cartesianism embedded a new Platonism in the heart of the West, one which severed its last connections to the vital by sloughing off the religious and ethical precepts that structured man’s intellectual life. (Barrett would wrestle with the history of modern philosophy right up until his last book, Death of the Soul.)

On the other hand, Barrett links the first impulse, Hebraism, with existentialism. “The features of Hebraic man,” he writes, “are those which existential philosophy has attempted to exhume and bring to the reflective consciousness of our time.” The philosophical figures that have haunted all of Woody Allen’s works – e.g., Nietzsche in Hannah and Her Sisters and Dostoevsky in Love and Death – are presented as exemplars of the concrete. Though widely divergent in their religious and moral outlooks, the existentialists countered the Enlightenment ideal of reason and science with matters that struck to the core of “the whole man” – matters like alienation, anxiety,freedom, suffering, finitude, and death.

This analysis is striking for three reasons. First, it presents itself as a comprehensive account of the history of ideas. Barrett obliterates the notion that existentialism was a mid-century French fashion or literary movement, and instead situates it at the heart of the West’s struggle to understand itself.

Second, unlike “subtraction” histories that divide the West “laterally” into a bygone age of faith and the present age of unbelief, Barrett’s “vertical” division accounts for the variety of religious beliefs across the philosophical spectrum. It’s true that he sees both Judaism and Christianity (especially the bloodline of Paul, Augustine, and Pascal) as basically existential. “Though strongly colored by Greek and Neo-Platonic influences,” Barrett writes, “Christianity belongs to the Hebraist rather than to the Hellenist side of man’s nature because Christianity bases itself above all on faith and sets the man of faith above the man of reason.” Still, Hellenists and Hebraists each have their figures of faith (Kant v. Kierkegaard) and unbelief (Hume v. Nietzsche), which is still very much the case today.

Third, Barrett doesn’t frame this division as inevitable. From the beginning, he admits that there is an innate disposition in Hebraism toward the rational:

“We have to insist on a noetic content in Hebraism: Biblical man too had his knowledge, though it is not the intellectual knowledge of the Greek. It is not the kind of knowledge that man can heave through reason alone, or perhaps not through reason at all; he has it rather through body and blood, bones and bowels, through trust and anger and confusion and love and fear; through his passionate adhesion in faith to the Being whom he can never intellectually know.”

He also sees an innate disposition in Hellenism toward the vital:

“While existential philosophy is a radical effort to break with this Platonic tradition, yet paradoxically there is an existential aspect to Plato’s thought…we have to see Plato’s rationalism, not as a cool scientific project such as a later century of the European Enlightenment might set for itself, but as a kind of passionately religious doctrine – a theory that promised man salvation from the things he had feared most from the earliest days, from death and time.”

The Hellenistic and Hebraic impulses then forged an “uneasy alliance” in Augustine, later cultivated by the “unbounded rationalism” of medieval thinkers for whom faith was “beyond reason, but never against, or in spite of it.” In short, Christendom gave us peacetime in the great battle of the vital and rational:

“St. Augustine saw faith and reason – the vital and the rational – as coming together in eventual harmony; and in this too he set the pattern of Christian thought for the thousand years of the Middle Ages that were to follow…dogmas were experienced as the vital psychic fluid in which reason itself moved and operated and were thus its secret wellspring and support…The moment of synthesis, when it came in the thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries, produced a civilization perhaps as beautiful as any man has ever forged, but like all mortal beauty a creature of time and insecurity…”

For Barrett, the medieval synthesis was shattered by a battle between intellectualism (the entrenchment of the rational) and voluntarism (a resurgence of the vital), part of a broader disagreement between Thomists and Scotists that helped launch both Protestantism and Rationalism. Protestantism “placed all the weight of its emphasis upon the irrational datum of faith, as against the imposing rational structures of medieval theology”. Rationalism, on the other hand, removed reason from the “psychic fluid” of the vital, leading us to the “bitter end of the century of Enlightenment” where “the limits of human reason had very radically shrunk”.

In the end, Barrett would take the fideism of a Kierkegaard over the rationalism of a Hume any day, and to understand Barrett’s rallying cry is to understand Woody Allen: “We have to establish a working pact between that segment [reason] and the whole of us; but a pact requires compromise, in which both sides concede something, and in this case particularly the rationalism of the Enlightenment will have to recognize that at the very heart of its light there is also a darkness.”

Still, if Barret is right – and I think he is – it goes both ways: a vitalism without reason is as blind as a rationalism without vitality is volatile. The existentialists are right that there’s more to life than rationality; but if pure reason leaves us cold, pure vitality burns us up. Both sides of our being long not just for a compromise but an integration. We long to be both fully vital and fully rational. For that reason I don’t think it’s a coincidence that Catholicism haunts so many of Woody Allen’s films. Following the logic of the Incarnation, Catholic Christianity has always striven to achieve a “both/and” with regard to the rational and suprarational, a kind of hypostatic union of the mind that – so long as we’re committed to defending it – will make us whole again.

Related Posts

Note: Our goal is to cultivate serious and respectful dialogue. While it's OK to disagree—even encouraged!—any snarky, offensive, or off-topic comments will be deleted. Before commenting please read the Commenting Rules and Tips. If you're having trouble commenting, read the Commenting Instructions.